With the question of efficiency at the forefront of medical treatment, both doctors and patients want to get the most positive health results for their time, resources and money. This is especially true for common cancers such as melanoma where patients of different risk levels require varying frequencies of subsequent check-ups to ensure the cancer has not returned and to check for new melanomas.

A team of scientists from the University of Sydney, supported by the Melanoma Institute Australia, examined data from over 1,200 patients who had previous melanomas and developed a risk prediction model that looked at the absolute risk of subsequent melanomas. The model was created with a number of aims including tailoring patient cancer surveillance, communicating the individual risk of gaining another melanoma, and improving patient education.

The need for better cancer guidelines

Dr Anne Cust, lead author of the paper1 told Lab Down Under that despite being a common cancer in Australia, data on the risk of subsequent melanomas was lacking.

“There are quite a few people in the population that have had a melanoma but there aren’t good guidelines around what sort of follow up they should receive in terms of skin checks to look for a new melanoma. We did this study to better identify people that are at particularly high risk of developing another melanoma once they’ve already developed one or more,” she said.

The study took data from 1,266 patients in NSW who had melanoma between 2000 and 2003. The data from these individuals was identified in the NSW Cancer Registry and used in the international Genes, Environment and Melanoma (GEM) study – a global research effort which includes over 3,500 participants comparing those with only one melanoma and those with multiple.

This risk model, created for those who have previously had a melanoma, will be used in practice at the Melanoma Institute Australia alongside a previously constructed model for individuals who have never had one. Patients will fill out a small questionnaire to guide how often they need to return for a skin check in future.

“Some people get too many skin checks and some people don’t get enough. Our model tries to better match people’s risk with how often they come in for appointments. Some people could go less frequently and be seen by a GP in a general practice or a skin cancer clinic while others at higher risk may benefit more from seeing the dermatologist and getting total body photography to help detect skin changes. We’re aiming to use this to tailor people’s care more appropriately,” Dr Cust said.

In total, the 1,266 participants examined in the study had just over 2,600 primary (new, separate) melanomas. Of these participants, 62 per cent were men and the median age of diagnosis for the first melanoma was 58.9 years. The number of melanomas per individual ranged between one and 16 with over half of those studied having more than one melanoma.

A high propensity for cancer

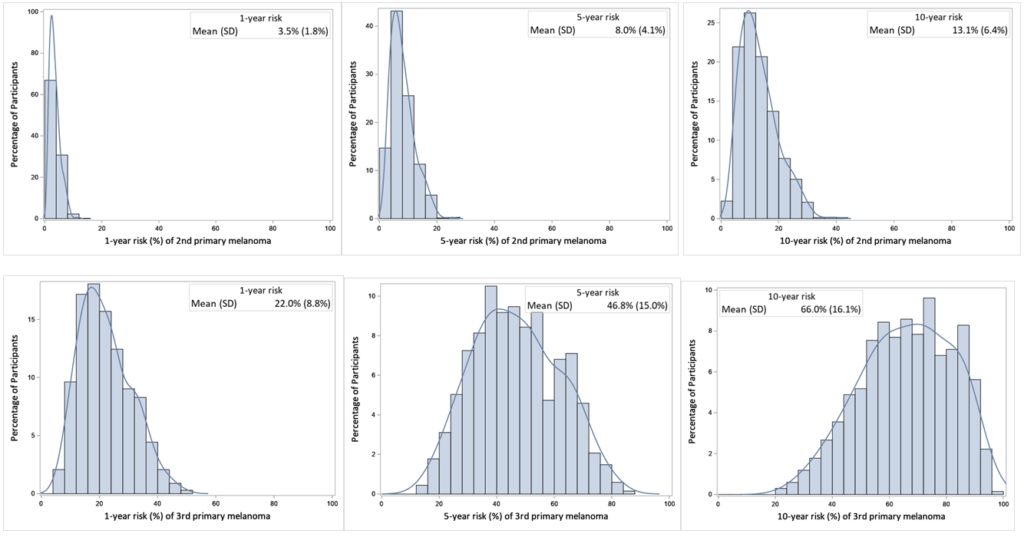

In the final risk prediction model, which included 12 risk factors, the mean absolute risk for developing a subsequent primary melanoma was 8.0 per cent for those with one, 46.8 per cent for those with two, and 52.5 per cent for those with three. Dr Cust suggested this large jump in risk between the first and second melanomas – but not the third and the fourth – reflected the predisposition of certain individuals to develop multiple melanomas.

“The risk factors influence whether you get another melanoma but then if you develop two melanomas, you’re much more likely to get another one than if you only have one. So I think it’s just reflecting that some people have a very high propensity for getting skin cancer,” she said.

The risk factors included in the model were the individual’s sex, age at first melanoma, previous keratinocyte cancers (such as basal cell carcinoma or BCC and squamous cell carcinoma or SCC), family history of melanoma, skin colour, mole density, ability to tan, a polygenic risk score, presence of a rare CDKN2A gene mutation, level of recreational sun exposure, and body type and histological subtype of any previous melanomas.

“The polygenic risk score measures the presence of common genetic risk factors for melanoma in multiple risk genes that have small but cumulative impact on melanoma risk, whereas mutations in CDKN2A are rare and carry a high risk of melanoma. Also if your previous melanoma was on the head or neck, you’re more likely to get another one than if the melanoma was on a different body site. That’s because head and neck melanomas often reflect people that have had a lot of sun exposure over their life,” Dr Cust said.

The risk prediction model also showed that the risk of subsequent melanomas was 4.75 times greater for those in the top 20 per cent of the risk distribution than those bottom 20 per cent.

“Even for people with the same number of melanomas, there’s a distribution or a spectrum of risk where some people have very high risk of developing a new primary melanoma and some people have low risk. People who have a higher risk are more likely to carry the risk factors that are in the model,” Dr Cust said.

Creating an accurate model

The model itself was found to be sufficiently accurate with a Harrell’s C-Statistic of 0.73 for predicting a second primary melanoma and 0.65 for predicting a third or fourth. The c-statistic is a measure of the ability of the risk model to discriminate between those who will develop another melanoma and those who won’t. The value lies between 0.5 and 1, with 1 indicating perfect discrimination.

“The c-statistic values for our risk prediction model compare favourably to models that have been developed for other cancers. Seventy-three per cent of the time, a person who develops a second melanoma will have a high risk score from the model than someone who does not develop another melanoma,” Dr Cust said.

The study’s risk model creates an estimated percentage risk for each person of getting another melanoma over the next 10 years, but that does not mean individuals assessed would definitely get skin cancer later on in life, she told Lab Down Under.

“Obviously it’s very hard to create a model that predicts with 100 per cent accuracy that a person will or won’t develop something like colorectal cancer or breast cancer. So the higher the C-statistic, the better the model will be at making that estimate of your risk level.”

For comparison, previously developed primary cancer risk models produced average c-statistics of 0.63 for breast cancer, 0.70 for colorectal cancer, 0.70 for prostate cancer, 0.75 for melanoma and 0.78 for lung cancer.

Honing the model through future follow-ups

Once the model is implemented in practice, Dr Cust described plans to follow up those patients to see how accurate the model actually was at predicting the risk of subsequent melanomas. In this way, the risk model can continue to be evaluated and improved upon.

“We’ve developed the model from a study of over 1,000 people and over 2,000 melanomas but what we’d like to do is further validate that model in the clinic. So we’d like to collect that data over time to see how well it predicts development of new melanomas and if we need to make any adjustments to the risk model, we can do that or perhaps we can add new risk factors as they become available,” she said.

The University of Sydney is already working with the Melanoma Institute Australia to put this further follow-up research into place and has gained ethics approval from the University Ethics Committee. This second phase is predicted to commence in the coming six months.

Current guidelines in Australia for melanoma follow-up are based more around detecting spread of melanoma rather than detecting new primary melanomas, with more frequent follow-ups for those with more advanced disease at diagnosis.

The model developed by the University of Sydney enables follow-up guidelines to be tailored. The research team hopes that their preliminary research will lead to larger studies and changes to the clinical management guidelines in the future. Those who have or suspect they have a melanoma should always speak to their physician for actual medical advice.

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 A risk prediction model for development of subsequent primary melanoma in a population-based cohort, British Journal of Dermatology, Sept 2019

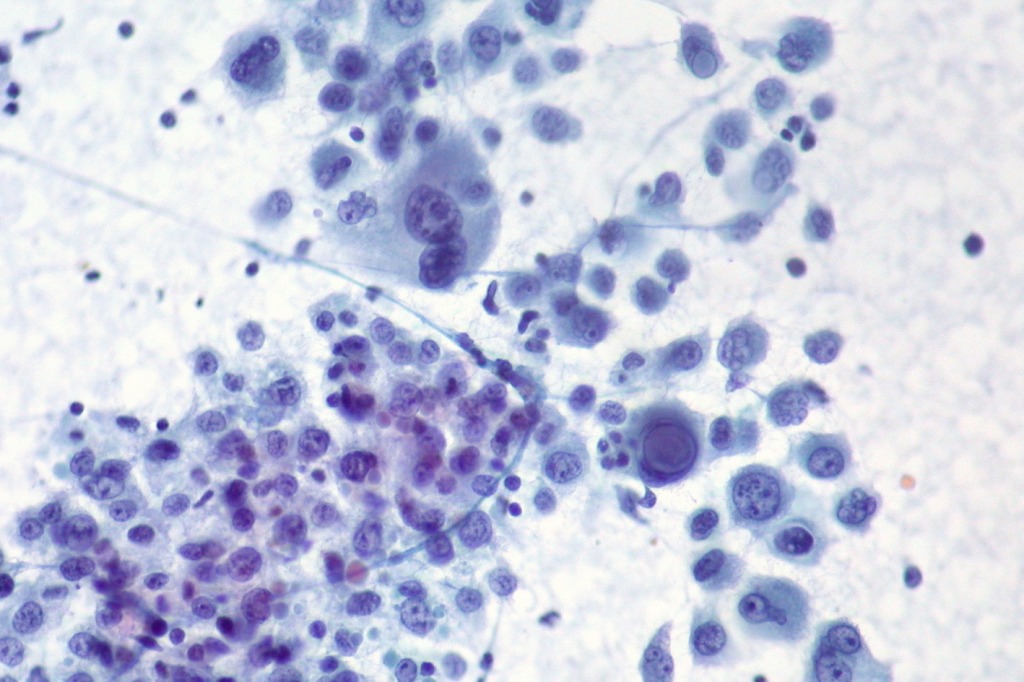

Featured image: Malignant Melanoma, Liver FNA, Direct Smear, Pap Stain. Picture by Ed Uthman used under the 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licence.