Individuals with chronic heart failure are not experiencing effective rehabilitation and tens of millions of dollars are being wasted in medical costs in part because of poor health literacy among Australian health professionals, a new study has suggested.

The research, conducted jointly by a team at Monash University and Australian Catholic University, surveyed 165 cardiac and chronic heart failure rehabilitation programs across the country and uncovered numerous barriers to patients’ engagement in these programs.

As well as because of poor health literacy of medical staff, the study found that engagement was adversely affected by a lack of flexibility in programs which should focus specifically on those with heart failure as opposed to cardiac problems in general.

Katie Palmer of the School of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health at Monash University was lead author of the paper1 and talked to Lab Down Under about what could be done to encourage heart failure patients to attend rehabilitation and how this could help drastically reduce Australian healthcare system costs.

‘Heart failure’s quite a scary term’

With over half a million Australians in a growing population of individuals with chronic heart failure, Palmer decided to examine the barriers people face when attending and completing rehabilitation to improve quality of life and physical ability, and maximise the amount of time spent out of hospital.

In the survey, Palmer and her team received responses from program coordinators like registered nurses and physiotherapists at 165 rehab programs nationwide found through the Australian Cardiac Rehabilitation Association database.

The responses revealed that not only had many medical staff failed to offer patients accurate information about their condition but many health workers failed to refer individuals to rehab programs in the first place.

“We found that quite often, patients didn’t actually know anything about their condition. Heart failure’s quite a scary term. It’s not really the best named condition in terms of trying to motivate someone because most people’s basic understanding is that it means they’re dying,” Palmer said.

Not only were people ill informed about what their condition was, they also weren’t told how exercise could assist, she added.

“We found a lot of people didn’t have that education. They didn’t get that when they were in hospital for their first, second or seventh admission with heart failure symptoms. They weren’t being told what else they could do.”

An unawareness of research trends

A lot of cardiologists and other medical professionals didn’t refer patients to rehab because they hadn’t been informed about the latest heart failure research, Palmer told Lab Down Under.

“These professionals in fact didn’t actually understand the changes that had been shown in the last 15 years that rehab is safe for someone with heart failure, that it is really effective.”

Palmer suggested that this gap could stem from a change in paradigm in the medical field regarding heart failure and rehab. While 20 years ago there was no evidence that those with heart failure could exercise safely, this had changed recently with studies showing exercise such as hydrotherapy could be done safely, she said.

Since people with heart failure didn’t used to live that long, there was a dearth of research in the past around what to do with these patients to keep them alive, Palmer said, adding that this had completely changed now.

“Before our medical management got so much better, before we understood what was going on, you died. That really is just what happened unfortunately.”

The results matched with what Palmer had seen anecdotally in her time working as a physiotherapist at rehab centres in Melbourne.

“People were telling us when they came to see us at rehab at our health centre that the doctor had told them, ‘Don’t go too hard, don’t do anything, just rest’. And that’s quite an old message these days.”

Instead, some level of exercise has been shown to be beneficial to those with chronic heart failure, regardless of how severe their condition is, and can boost their quality of life and help maintain independence for longer.

“I found it quite interesting that that the medical professional level of knowledge towards things that weren’t medicine or pharmaceutical treatment was still quite low. I found that surprising,” Palmer said.

Systematic and individual barriers

The survey also uncovered gaps in the system itself even for medical professionals who were aware of the benefits of exercise for chronic heart failure patients.

For instance, medical professionals could simply be unaware of the available rehab options in the area and thus failed to properly refer out patients when able to do so.

“There were lots of survey comments about breakdown of referrals — referrals not being sent to the right place and so never being received. Then in terms of service provision, once the referral got there, a lot of the time there was such a long waitlist because the centre didn’t have enough resources for the number of patients that they were seeing,” Palmer said.

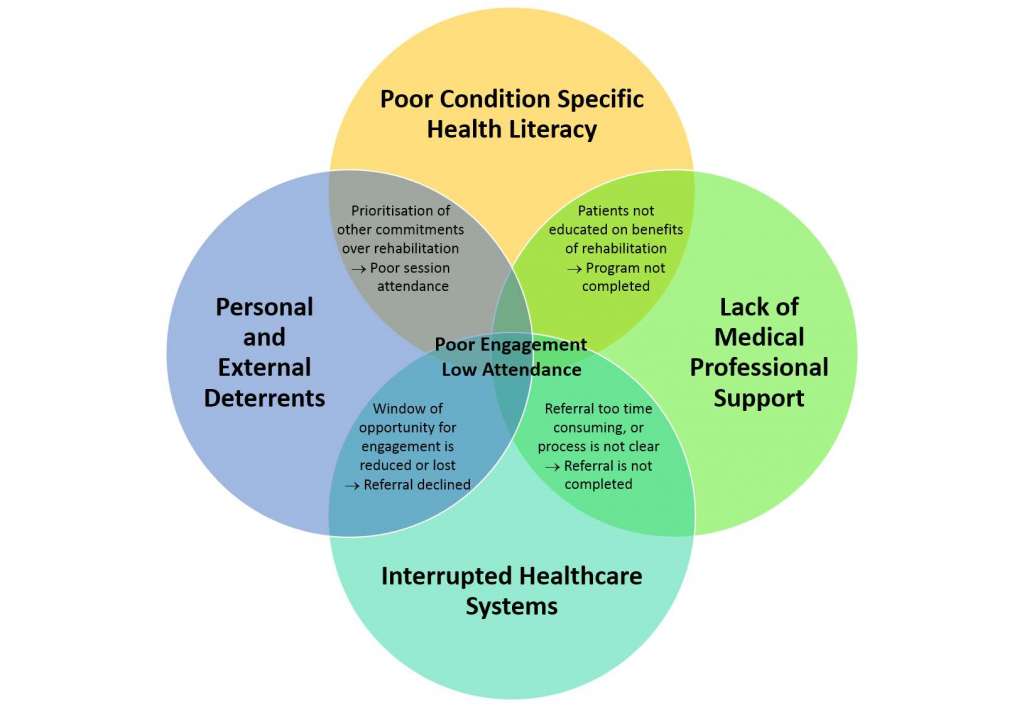

Figure 1: Interrelationship of thematic barriers leading to reduced engagement in chronic heart failure rehabilitation.

A further issue was that many rehab programs were not what is known as ‘condition specific’, i.e. tailored to a specific medical condition. This meant that a lot of rehab programs were offered for both chronic heart failure and acute cardiac conditions such as heart attacks, valve replacement and open heart surgery — a divergence of goals which could cause problems, Palmer said.

“Our goal with acute cardiac patients is to help them work a little harder, reach that moderate intensity and build an active lifestyle. With something like heart failure, we’re really looking at maintaining what they’ve got and teaching them self-management for their chronic condition. So when you’ve got a combined group of heart failure and cardiac, the message is very different.”

On top of this were further barriers experienced by the patients themselves to actively attend and persist with rehab. These could include the individual feeling too unwell to participate, the juggling of other priorities such as family, and accessibility concerns such as how far parking was from the centre.

Short-term cuts over long-term savings

With these inefficiencies in the system and a growing population of those with chronic heart failure, Australia’s healthcare system was being burdened with far higher costs than needed, the research suggested.

As of 2017, there were over 511,000 people with chronic heart failure in Australia with a national healthcare cost of $3.1 billion2 that included $2 million from the 158,000 hospital admissions each year. These figures are projected to increase, research suggests, with Australia predicted to have a further 657,000 new cases of chronic heart failure by 20252.

With rehab’s ability to help those with chronic heart failure maintain healthy lifestyles and avoid expensive hospital visits, even an increase of referral rates to 65 per cent could help the Australian healthcare system save another $86 million3.

Despite this, Palmer’s research showed that rehab programs were being cut across Australia.

“People who were registered on the Australian Cardiac Rehabilitation Association database as a program that provided heart failure rehab contacted us to say they weren’t running anymore, their funding had been cut, their program had been closed, which is actually really alarming.”

With less than a 50 per cent response rate in the survey already, it was possible to theorise that some of the remaining half of programs contacted had also shut down, Palmer said.

“How many of those had actually closed in the years since the database had last been updated? Maybe the services of a lot of those who didn’t get back to me at all, they could be closed programs. What’s that saying about our service provision if we’ve got programs closing when our incidence of this disease is only rising?”

Adding funding and putting more people through condition specific heart failure rehab programs could reduce the amount of hospital admissions in future, Palmer said.

“Those hospital admissions can obviously cost quite a lot of money. If someone’s having up to two or three admissions per year — quite possible for those with heart failure — we could be saving a lot of money by keeping those community programs open.”

Overcoming barriers, doing it right

To provide more data about the barriers to rehab, Palmer is currently conducting more research in the area, interviewing chronic heart failure patients and gathering data that complements those gained from her survey of health professionals.

These interviews will examine topics such as what patients know about their condition, what their previous experience with exercise was, and what their experience with rehab was if they attended. Discussing things like the reasons for going to rehab or staying home, and what aspects made it easier to stick with rehab were important, Palmer said.

“I want to make sure that, as health professionals, we’re not missing anything. I want to make sure that if recommendations need to be made so that services are redesigned, that they get redesigned in the right way. We need do it in the right way for the person because it doesn’t matter what the health professional wants or what suits the hospital or the centre itself. It really needs to suit the person or it’s not going to work.”

Further marketing needed to be conducted of heart failure itself too because it was not a well-known condition among the public, Palmer said.

“A lot of people don’t know about it and if we don’t know about it, how can we support people that have it, if no one really understands it and they’re scared of it? I would have loved a name change too. Heart failure’s just a terrifying term, but it’s a bit late for that.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Palmer K, Bowles K, Lane R, Morphet J. Barriers to Engagement in Chronic Heart Failure Rehabilitation: An Australian Survey. Heart, Lung and Circulation, August 2019.

2 Chen L, Booley S, Keates AK, Stewart S. Snapshot of heart failure in Australia. May 2017. Mary MacKillop Institute for Health Research, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia.

3 De Gruyter E, Ford G, Stavreski B. Economic and Social Impact of Increasing Uptake of Cardiac Rehabilitation Services – A Cost Benefit Analysis. Heart, Lung and Circulation. Volume 25, Issue 2, February 2016, Pages 175-183.

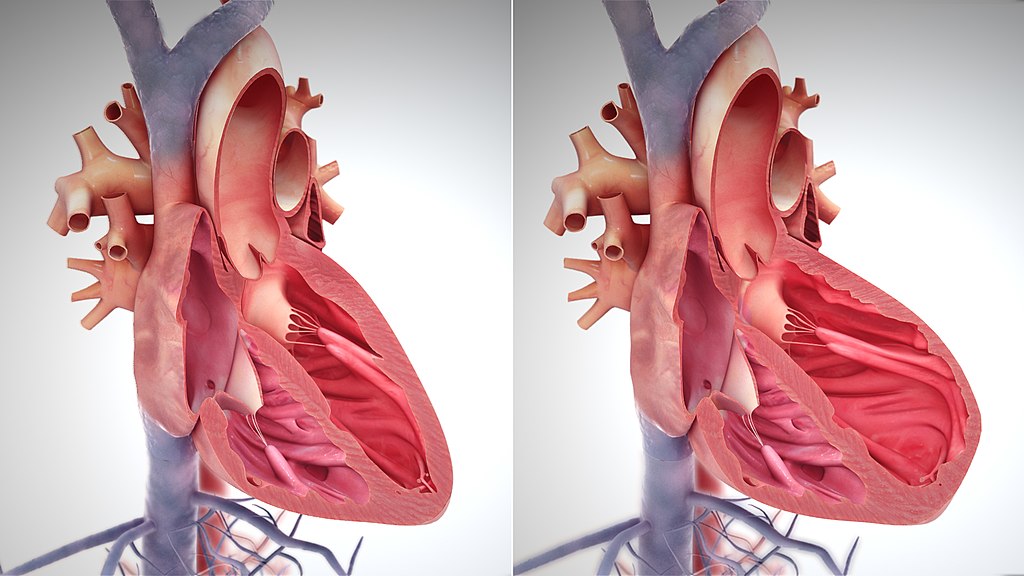

Featured image: A depiction of heart enlargement during heart failure. Picture by Scientific Animations used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.