With Indigenous Australians often forced to choose between keeping native title and receiving public healthcare, some remote communities have had to think outside the box and get creative when it comes to providing medical care, new research has found.

The paper1 argues that the Australian Government should revisit its obligations to remote-living Indigenous Australians, who are often burdened with high rates of chronic disease and disabilities, and supply healthcare that is easily accessible and culturally-appropriate.

Dr Nina Hall of the University of Queensland’s School of Public Health, who worked on the research with Professor Sandra Creamer, international indigenous rights leader and interim CEO of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women’s Alliance, told Lab Down Under about the gaps Indigenous Australians can face regarding access to healthcare and the innovative solutions they had used to overcome these.

Government services supplied at a cost

Whether health services were offered on remote lands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples often came at a compromise, with the holders of that land sometimes being required to forgo their native title rights and cede some control over to the government setting up the hospital or clinic, Dr Hall said.

Under native title, Indigenous Australians receive recognition of their long-term ownership and access to traditional lands although their rights fall short of actually being able to commercialise or sell the land itself.

The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery is an agreement offered by the federal, state and territory governments to provide public services in remote communities in exchange for some level of signed over control to that traditional land, Dr Hall said.

“Perhaps the government feels that native title is a security risk or a risk to the stability of that service delivery. And so the most stable way they can achieve that is to have a signed commitment from those traditional owners that they have a lease that’s long enough to be worthwhile making this investment.”

Dr Hall noted that this type of agreement could really limit the land rights that Indigenous Australians had worked so hard to gain through native title.

“Indigenous organisations have gone on the record saying this really limits their self-determination and that the community has to weigh up whether they cede some of their control in local decision-making in return for services such as health services.”

The conflict between native rights and government control of the land has been shown by Australia’s initial reluctance to join 143 countries in signing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in September 2007.

At the time, the Coalition government, led by John Howard, saw the declaration as placing customary law over national law, particularly with regards to the ownership and control of land. This position was reversed however and the declaration signed in 2009 after Labor’s Kevin Rudd took over as Prime Minister.

“It does put in a very stark situation how concerned the government is about who controls the land, who makes the decisions about the land, and then it comes down ultimately to healthcare and many other things,” Dr Hall said.

There was a disconnect with the Australian government’s responsibility to “close the gap” and increase access to quality health services to reduce disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, the research found.

“Given the cultural diversity of Australian Indigenous Peoples, the government, as the duty bearer, needs to demonstrate accountability by negotiating with the traditional owners who hold the right to decisions on the development and improvement … in remote Aboriginal communities, especially around state borders,” the paper said.

Strengths, deficits and a burden of disease

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience a higher rate of chronic disease and disability than the general population, Dr Hall told Lab Down Under that this was only one way of looking at overall health in these communities.

One perspective to admire, she said, was that there was still a growing population of proud Indigenous Australians who have a connection to country and who know their history and culture, despite a concerted effort by successive governments since colonisation to remove people from their traditional lands through policy eras such as the Stolen Generation.

These positive aspects play a large part in the overall health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, Dr Hall said.

“When we talk about health, there are so many different perspectives we can take. We risk, as non-indigenous people, thinking in a very western way which is very much about what’s the disease and how many people have got it?,” she said.

“That is definitely one way of measuring health, but with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, it’s much broader, much more holistic. It’s not just about the individual, it’s about the community so there’s a lot that’s so powerful and so strong.”

Connection to family, extended family, community and to country itself, is also vital to Indigenous health, both mental and physical.

However, Dr Hall noted that, when health was examined at an individual level, nearly half the Indigenous population, including adults and children, reported having a disability or a long-term chronic disease2.

As a case study, the research examined chronic kidney disease for which one in five Indigenous adults had indicators of or had the actual disease3. This was four to six times higher than the general population, Dr Hall said.

Facing barriers and overcoming them

With a two-hundred year long history which has resulted in a mistrust of most things associated with government, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can sometimes fear engaging with the western medical system because of direct racism that they had experienced there.

“Many Indigenous people have described that they don’t feel there’s a place for them in a hospital. They don’t feel they’re respected. They don’t necessarily speak English as a first language and there’s not necessarily a translator or a cultural worker there to be an ally,” Dr Hall said.

However, these obstacles had led to the creation of unique entities such as Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) which are run by Indigenous Australians and which offer healthcare in a culturally-appropriate manner.

Receiving funding from Medicare, ACCHOs treat the health of patients while also examining factors in individuals’ homes and lives that may be contributing to disease. This could include the number of people living in the same house and whether there was access to working facilities such as toilets and showers.

“It’s really looking at the household and community as a whole and not just writing a prescription. While it is important to have medication when you’ve got ill health, it’s also important to start thinking about what’s behind that. How can it be better managed? How can it be prevented?” Dr Hall said.

Art, dialysis and self-ownership

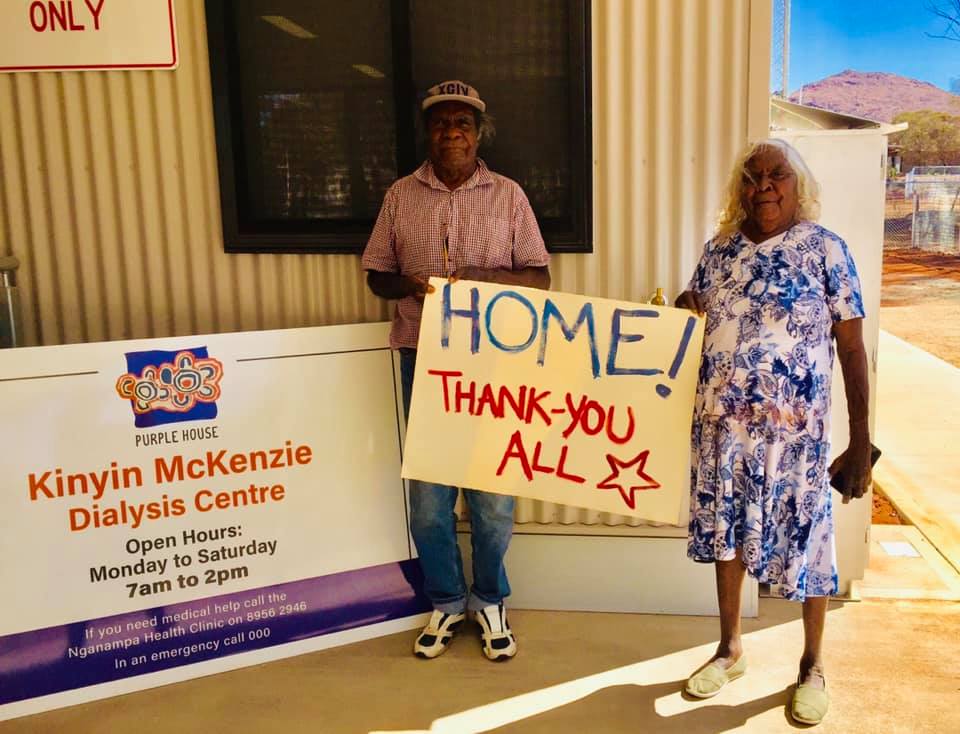

In their research, Dr Hall and Creamer described a display of resilience in the Western Desert peoples who managed to form their own community-controlled medical centre to provide kidney dialysis to those in tiny, isolated communities spanning remote areas in Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

While these communities experience high rates of chronic kidney disease, especially in their population of elders, the government was reluctant to provide dialysis services to such remote townships and the people did not want to give up their native title in exchange for such services.

To solve this dilemma, the local Aboriginal peoples came upon an alternative solution, holding an artwork auction supported by the Art Gallery of NSW and Sotherby’s to raise enough money to buy a number of dialysis chairs and pay the full-time wage of a qualified nurse.

“That’s a story that’s so positive. It’s about a community confronting the chronic disease that’s suffered by a lot of people in their community, but it’s about saying no to losing their rights to their land and it’s about controlling their health on country,” Dr Hall said.

The resultant entity, called the Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tjutaku Aboriginal Corporation, now operates a clinic called the Purple House in Alice Springs as well as a mobile dialysis unit called the Purple Truck and 18 dialysis units in remote communities.

Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tjutaku comes from the Pintupi language and is translated into English as ‘Making all our families well’.

Image: Purple House’s Yari Yari Zimran Tjampitjinpa Dialysis Centre, named after a Pintupi Elder who helped initiate the service but who passed away from chronic kidney disease. Used with permission.

Other initiatives such as the Inala Indigenous Health Service provide culturally-appropriate healthcare in a suburb that currently has the largest population of Aboriginal people in Brisbane.

“The clinic staff spend a lot of time on patients who really do need hospital care engaging with them about what to expect in hospitals, how their data will be used, how there’s no risk of their children being put into foster care — all fears that are well-founded over history — just to build that sense of safety that you can go from this clinic that is culturally safe to a big hospital that can be quite daunting,” Dr Hall said.

Honest conversations on racism and history

Dr Hall said that Australians needed to be aware of the differences that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had when it came to accessing and experiencing healthcare and the cultural and historical reasons for that.

One common assumption that those who were sick would want to go to the big city and get treatment could overlook Indigenous Australians’ connection to country, Dr Hall noted.

“Many of us who are migrants to Australia, we lost our traditional land long ago somewhere overseas. We actually don’t know what that connection feels like. So I think it requires non-Indigenous Australians to be quite open-minded about other cultures, especially our First Nations Peoples, and accept to ourselves that maybe we don’t get it. We have to be open to just acknowledging there are other ways of seeing, other ways of knowing.”

Negative historical impacts from Australian chapters such as the Stolen Generation are still being felt in communities today through effects such as higher obesity, smoking or drinking rates.

“We are all a product of our history in terms of our health and many other dimensions of our lives. And while we’re sitting here in 2020, the impacts of history still remain today,” Dr Hall said.

Even small changes like hiring an Indigenous Australian as a receptionist, displaying Aboriginal artwork in the waiting room, or broadcasting Indigenous television or radio have been noted by clinic clients to make a huge difference, Dr Hall told Lab Down Under.

“Just giving a strong nod to proud cultures can make it feel like a place you would want to go where you don’t experience racism and you’re not going to be judged. You’re going to actually be supported, which is what we would hope the health system does,” she said.

“Awareness is a big step and respect is a really important value. Humility too by those of us who are in the dominant position, either through the colour of our skin, our first language or our financial resources. There are so many ways that non-Indigenous Australians are dominant. It’s our responsibility to make sure that services are reaching everyone. As the United Nations has stated in its Sustainable Development Agenda that Australia has signed, there should be no one left behind.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Creamer S, Hall N. Receiving essential health services on country: Indigenous Australians, native title and the United Nations Declaration. Public Health, Volume 176, November 2019, Pages 15-20.

2 United Nations General Assembly. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples on her visit to Australia. New York: United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council; 2017. Thirty-sixth session, 11-29 September, Agenda item 3.

3 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australia Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey. Biomedical results. Canberra: Australia Bureau of Statistics 2014; 2012-13 (Report No: 4727.0.55.003).

Featured image: William Sandy and Tjunkaya Tapaya at the Purple House dialysis centre at Pukatja (Ernabella) in South Australia. Used with permission.