While inhalation injuries are known to lead to poorer outcomes for burns patients, there is no consensus among Australian and New Zealand medical professionals about how these injuries should be diagnosed, new research has found.

The paper1, published by scientists at Monash University, examined data from eight adult burn centres across Australia and New Zealand and found that the actual rate of inhalation injuries varied depending on the different diagnostic criteria used.

Dr Lincoln Tracy and Dr Heather Cleland of Monash University were part of this research and talked to Lab Down Under about why this variation was detrimental to burns victims and why there was a need for a standardised set of assessment criteria across the two countries.

A ‘problematic’ variation in diagnosis

As well as suffering external heat burns, those exposed to fire can injure their airways through the inhalation of hot ashes or toxic smoke. These injuries occur in between five and 35 per cent of burns patients and are what is known as prognostic, in that they can be used to estimate how likely an individual will recover.

“There are several studies showing that inhalation injuries are associated with an increased risk of mortality,” Dr Tracy said.

To identify the documented incidence rates of inhalation injuries locally, the researchers examined inhalation injury data from more than 11,000 patients found in the Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand (BRANZ) and collected between July 2009 and June 2016.

While BRANZ contains data from 17 designated burns units, eight units who treated adult patients and provided ICD-10-AM codes to the registry were used for the study. ICD-10-AM is a classification system created by the National Centre for Classification in Health that contains a tabular list of disease.

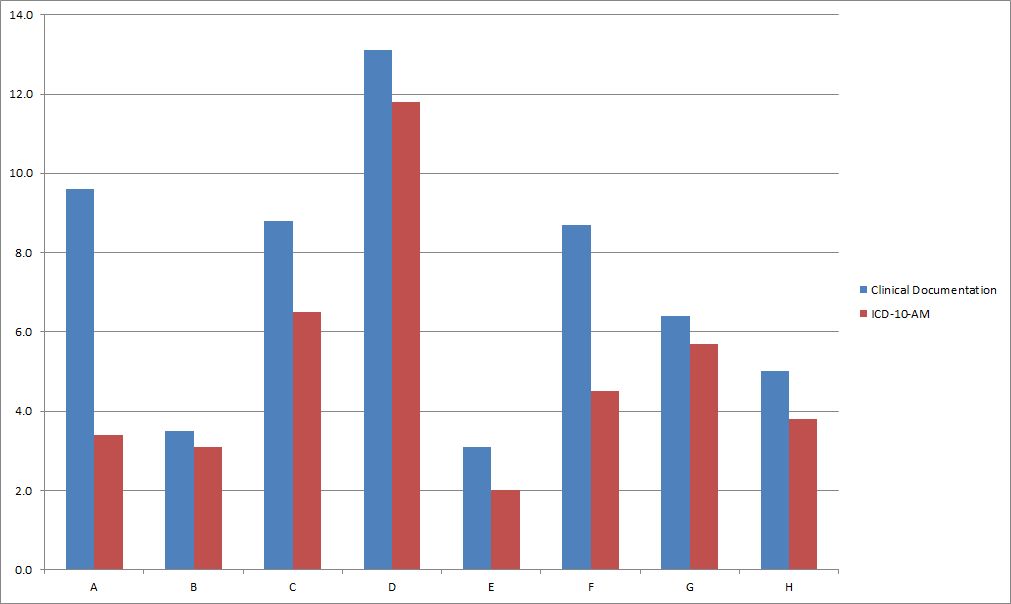

“We found that there is a difference in the reported incidence of inhalation injuries across the adult burns units in Australia and New Zealand, even after adjusting for relevant demographic and injury event characteristics,” Dr Cleland said.

This was an interesting finding because it flew against the assumption that incidence rates across all burns units would be similar.

“The observation of variance between the sites suggests that different units are using different definitions and diagnostic criteria for inhalation injury when assessing their patients,” Dr Cleland said.

Image 1: Prevalence rate of inhalation injury in adult burns patients from eight burns units comparing BRANZ inhalation injury field documentation with ICD-10-AM codes. Data by Monash University. Used with permission.

This type of variation in the definition and diagnosis of inhalation injuries could be problematic, Dr Tracy told Lab Down Under.

“This means that inhalation injuries can either be over- or under-diagnosed, which has carry-on implications in ensuring patients receive the appropriate treatment for their injuries.”

Obstacles to a proper consensus

While diagnostic criteria and clinical consensus statements on inhalation injury have been previously published, actually accepting these can be difficult in part because of the subjectivity involved in assessing these types of injuries through a physical examination of the face and respiratory tract.

This subjective nature applies even when using more ‘objective’ measures such as a fibre optic bronchoscopy during which a thin flexible camera is passed down the throat and into the lungs.

“Either end of the spectrum – very severe or absent inhalation injury – is usually straightforward to identify. However, determining grades of severity of an inhalation injury is much more complicated – there is a lot of grey area in this space. This makes the assessment and diagnosis of inhalation injuries very subjective,” Dr Cleland said.

Further complications in assessing inhalation injuries arise from the different types that can occur (including thermal burns to the airway or the inhalation of toxic chemical fumes) as well as their dynamic nature, with how they look changing over time.

The actual rate of inhalation injuries could also vary depending on a number of factors, Dr Tracy said.

“First, it depends on your patient population. If you examine patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit, your observed rate of inhalation injury will most likely be elevated as these patients typically have more severe injuries than other patients do.

“Second, given the subjective nature of the assessment and diagnosis of inhalation injuries, different clinicians could draw different conclusions from examining the same patient. The list goes on.”

The burning issue of an agreed protocol

If a more standardised assessment criteria could be implemented however, this would then result in a more consistent comparison between burns units and enhance the prognostic effectiveness of these types of medical diagnostics, Dr Cleland said.

“In order to compare outcomes between units and monitor the effects of different treatments for quality of care improvements, it is necessary to ensure we are treating the same patients. Inhalation injury is particularly important in this context because we know at the more severe end of the [burn injury] spectrum it exerts a significant influence on major outcomes, such as mortality.”

While standardised criteria are being used in other parts of the world, Australia and New Zealand have not yet come to an agreement in this area, he added.

“For example, it is not routine practice across all units to use a bronchoscopy to assess inhalation injury severity.”

With this variation in documented inhalation injury rates uncovered by the research, Dr Tracy said the next step would be to analyse which practices are used to assess and diagnose inhalation injury in BRANZ burns centres.

“From there, we can establish an agreed protocol for the assessment of inhalation injury across Australian and New Zealand burns units. Studies such as these show the value of a clinical quality registry. It allows us to identify clinical issues that can be followed up at an individual unit level to improve patient care.”

BRANZ itself is a collaboration between the Australian and New Zealand Burn Association (ANZBA) and Monash University’s Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine.

Dr Tracy works for Monash’s School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine while Dr Cleland is an Adjunct Clinical Associate Professor at Monash’s Central Clinical School and is the Head of the Victorian Adult Burn Service at Alfred Hospital.

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Tracy L, Dyson K, Le Mercier L, Cleland H, McInnes J, Cameron P, Singer Y, Edgar D, Darton A, Gabbe B. Variation in documented inhalation injury rates following burn injury in Australia and New Zealand. Injury, 17 November 2019.

Featured image: House Fire. Picture by Adam Belles. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licence.