The discovery of swathes of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on social media platforms has led to calls by scientists for governments to monitor rumours and conspiracy theories online in order to create more effective public health messaging and ease the community’s concerns.

In new research, published in PLoS ONE in May1, an international multi-disciplinary team trawled social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and uncovered 637 rumours and conspiracy theories related to COVID-19 vaccination, most of which were false, misleading or exaggerated, and which had been liked and shared by approximately 103.3 million people.

Because this misinformation could lead to mistrust and vaccine hesitancy, the researchers recommended tracking it in real-time and disseminating correct information via social media in order to counter the negative effects this erroneous information was having on the public.

“We suggested that traditional methods of risk communication and community engagement should be explored to track and fact-check misinformation as ways to immunise people against misinformation and thereby pre-empt potential vaccine program disruptions,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

“Policymakers should consider these findings to devise risk communication and community engagement strategies to address these concerns with evidenced-based information.”

Dr Nusrat Homaira of the School of Women’s and Children’s Health at the University of New South Wales was co-author of the paper and talked to Lab Down Under about its findings and implications.

She described the research as “a massive undertaking” with multiple researchers in Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Myanmar and Thailand collaborating together by collecting misinformation spread through a range of online sources including Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, fact check agencies and television and newspaper websites between 31 December 2019 and 30 November 2020.

Conspiracies with an intention to harm

The most unusual conspiracy theories made wild claims that the vaccines contained microchips, altered our DNA, were operated by 5G networks, and were being used by people like Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates to control humanity. Other conspiracies mentioned the use of aborted foetal remnants in the vaccines.

Out of the over 630 pieces of disinformation, which were found in 24 languages from 52 countries, 91 per cent were defined as rumours while the remaining 9 per cent were conspiracy theories, Dr Homaira said.

Rumours could be true, false, misleading or exaggerated information that was made without any verified, authentic source. These were split into varying groups including claims regarding vaccine safety, accessibility and production. Conspiracy theories, on the other hand, were defined as disinformation disseminated by certain people or groups with an intention to harm.

“Misinformation generally doesn’t contain an intention to harm somebody. These are just things that are spread on social networks and different other platforms. They could be inaccurate, false or partially true,” Dr Homaira said.

“Conspiracy theories are claims that individuals and groups make, often to harm others. They could be absolutely false or have an element of truth to them but they are magnified by these groups or individuals with an intention to harm others.”

Video: Lab Down Under interview with Dr Homaira about COVID-19 vaccine rumours and conspiracy theories.

While anti-vaccination groups may argue with sentiments that the claims they propagate are harmful, Dr Homaira pointed out that vaccines themselves are a public health good which go through rigorous trials and are subject to rigorous regulation prior to being available to the public.

“Clearly when a vaccine comes into play, it is not intended to harm you because the scientific community would never let that happen. So when a minority of people spread propaganda to halter or affect that pathway, that is clearly an intention to harm,” she said.

Waves of disinformation correlate to pandemic’s spread

The researchers found the vast amount of misinformation was spread through three countries: the United States (15 per cent), India (13 per cent) and Brazil (12 per cent).

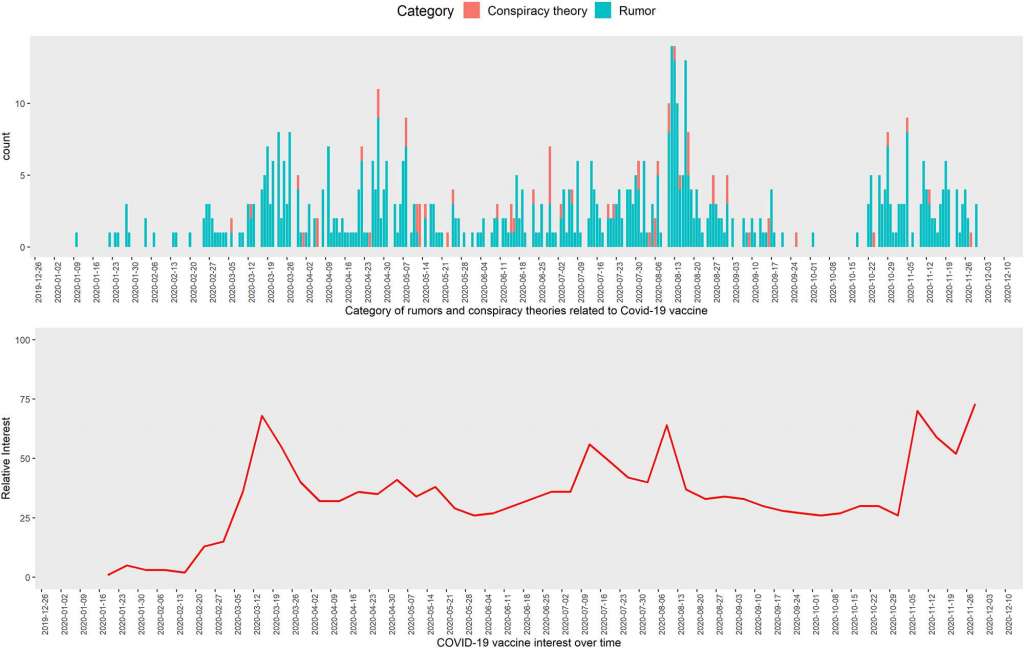

Between 10 January and 30 November last year, there were three “waves” of COVID-19 vaccine rumours and conspiracy theories, falling between February and May, June and September and October and November. The second wave boasted the largest spike of misinformation when compared to the first and third waves.

These waves correlated to the volume of internet searches for vaccines and lined up to the various waves of COVID-19 as it ran rampant through most of the world, particularly in countries with large populations such as the USA, India and Brazil.

“As the population gets severely hit by the pandemic, they also want a way out. Hence you see an association between the number of cases and people wanting to find out if there is a solution, vaccine or some treatment out of the problem. So I think that is why you see that peak and that co-relation between number of cases, the population affected, and also people’s need or hunger for an intervention to get out of this pandemic,” Dr Homaira said.

Image: Spread of misinformation and internet users search interest related to COVID-19 vaccines, 31 December 2019–30 November 2020. Used with permission. Click here for larger image.

Regarding the mode of dissemination, 61 per cent of these rumours and conspiracies were spread through Facebook while 28.6 per cent were disseminated through Twitter.

Dr Homaira noted that the researchers gathered data up until November 2020 which was before Facebook and Twitter announced they would be cracking down on COVID-19 “fake news” on their platforms.

“I think as these social platforms become more responsible in controlling what goes in and what goes out of those platforms, we are going to see an improved circulation of more claims of verified information,” she said.

Routine monitoring required for future resilience

With vaccines being our way out of the pandemic, inflated claims shared on social media, for instance around AstraZeneca’s very rare blood clots, were a concern and were affecting Australia’s vaccine rollout program, Dr Homaira told Lab Down Under.

For this reason, it was important for public health agencies to watch platforms such as Facebook and Twitter to follow the rumours and conspiracy theories being shared around, she said.

“I think it’s important that public health agencies keep in mind that they should have monitoring or surveillance of these platforms as a routine activity so that these types of misinformation, claims and rumours are picked up.”

The systematic monitoring of this misinformation could then be used to develop better public health messaging and engage with the community’s concerns both during the COVID-19 pandemic and in future health crises, Dr Homaira said.

“We should have a system in place to systematically monitor all the different misinformation and rumours circulating on social media. And not just for this pandemic but also for future health emergencies and health crises, because clearly this is not going to be the last pandemic.”

Dr Homaira hoped this pandemic would leave us more resilient to tackle future health emergencies that arise.

“All of us have someone who we have lost to this pandemic or was affected by the pandemic. So we should really learn from this, build on our experience and really leverage the capacity that has been strengthened to address this pandemic globally so we are much more resilient as a global population, and also as a country, to address future health crises.”

Language limits in online only research

While the research tried to be as extensive as possible, researchers were limited by the language of the rumours and conspiracy theories they could understand, with tools like Google Translate being unable to translate certain languages and dialects.

“We had that limitation where couldn’t translate those languages even though we tried every time we came across an international sort of misinformation claim,” Dr Homaira said.

The researchers also did not investigate rumours and conspiracy theories which were spread off the internet through avenues such as word of mouth. However, Dr Homaira noted this sort of misinformation would be similar to those spread online.

“I guess in this era of the internet, we are so active on social platforms. I don’t think the word of mouth rumours would have been vastly different from what we have picked up,” she said.

Further information about Dr Homaira’s research can be found through her Twitter feed, UNSW research and department of medicine webpages, Google Scholar, ResearchGate and LinkedIn account.

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube, Reddit and Twitter or support me on Patreon. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my blogs in your inbox.

1 Islam MS, Kamal A-HM, Kabir A, Southern DL, Khan SH, Hasan SMM, Sarkar T, Sharmin S, Das S, Roy T, Harun MGD, Chughtai AA, Homaira N, Seale H. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE 16(5): e0251605

Featured image: Fake News – Computer Screen Reading Fake News. Picture by Mike MacKenzie. Used under the Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licence.