A multinational survey has found that many Australian intensive care units reported suboptimal preparedness around personal protective equipment (PPE), including in relation to PPE training, practice and stock-awareness, around the time the COVID-19 pandemic commenced and were outperformed by their counterparts in countries like Singapore, Hong Kong and New Zealand.

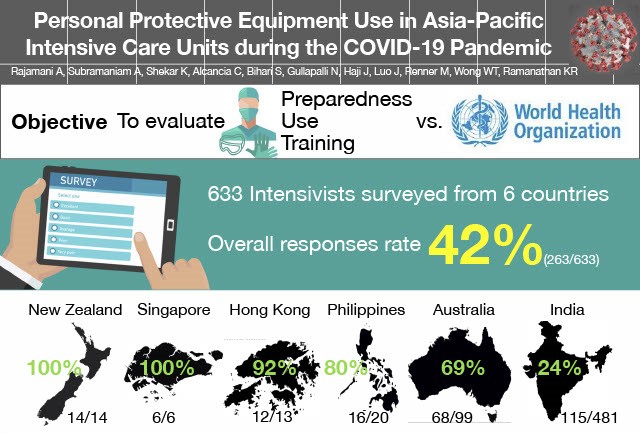

A recent paper1 released in Australian Critical Care detailed the results of the survey, which was conducted in over 600 ICUs in six nations across the Asia-Pacific region from March 25 to May 6 this year, and examined crucial healthcare areas such as adherence to the World Health Organization’s guidelines, training medical staff, procuring stock, and responding to suspected COVID-19 cases.

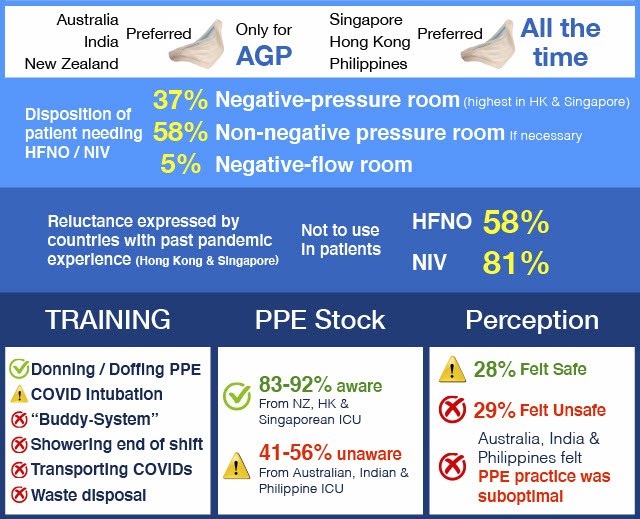

Overall, the study found that a greater proportion of ICUs in New Zealand, Hong Kong and Singapore had optimal preparedness than in Australia, India and the Philippines. Major areas of concern included suboptimal PPE training, poor resource management and inconsistent PPE guidelines across the globe.

Real data to test social media angst

Speaking to Lab Down Under, senior author Dr Arvind Rajamani of Nepean Clinical School at University of Sydney said one aim of the survey was to “give a voice based on data” after the commencement of the pandemic saw social media flooded with concerns about shortages of PPE and medical staff who were potentially left vulnerable to this highly infectious disease.

“There was a frenzy about COVID. There was a lot of angst about it on social media, particularly at that time because China was not exporting PPE. There was a significant supply shortage. While Singapore had seen this with SARS, Australia and New Zealand had never experienced anything like this.”

Senior author Dr Kollengode Ramanathan from the National University Hospital in Singapore said the study aimed to compare what was being projected in the media with what was actually happening in ICUs.

“The curiosity was mainly around the amount of media attention this was getting. When we looked at our own policies, we were not sure as to where we stood, and the initial literature search yielded nothing. Even in Singapore, we were doing a lot of preparation. We knew we had stockpiled PPE, but the feeling on the ground was never reflected in a big way in the media although there was a big hoo-ha about this.”

Image: Study infographic, part 1. Used with permission.

Many Australian and Indian ICUs not well prepared

The results showed that Australia and India were the most variable out of all countries surveyed regarding PPE preparedness, said Dr Rajamani.

“Australia and India were not well prepared as nations. There was a heterogeneity within those countries, so there were some hospitals in India and in Australia which were ticking all the boxes but overall as nations, they had the widest disparity,” he said.

While there were differences in guidelines between those issued by the WHO and those issued by national health bodies, even within Australia guidelines were also found to vary from state to state, district to district and even department to department in some hospitals.

“What we felt was there was a whole lot of confusion that came about because of differences between departments. I would use one type of mask in one ward but as soon as I turned into another department, I would need to wear a totally different set of PPE,” Frankston Hospital’s Dr Ashwin Subramaniam, who is senior author and adjunct senior lecturer at Monash University, told Lab Down Under.

Singapore and Hong Kong were universally prepared when it came to PPE training, stocking and management because the two nations had previous pandemic experience, thanks to the spread of SARS there in 2003.

“It looks like from the SARS experience they had invested in infrastructure, so they were using negative pressure rooms, they were using powered air purifying respirators, they were doing a lot of things by their previous experience,” Dr Rajamani said.

New Zealand was also consistently prepared, although this seemed to be because the country invested heavily in education and training.

Training and guidelines need improvement

The survey highlighted a number of areas that ICU staff would need to be trained in so that they utilised the available PPE in an effective and safe manner. This included the obvious steps of PPE donning and doffing — i.e. taking on and off the PPE — and other crucial areas, Dr Rajamani said.

“It’s also about transporting a patient from one part of the hospital to another, how cleaners are trained appropriately in PPE waste management and how family members are communicated with. How are they going to be protected? They could also potentially be a risk of infection to other people, so how can we protect ourselves from them?”

Proper training was difficult in a fluid situation like a pandemic, Dr Ramanathan said, so a concerted effort was required for hospitals to be prepared for a second or third wave.

Inconsistent PPE guidelines also fed into the confusion, Dr Subramaniam noted. By far the best guidelines out there were created by the Australia and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) as they were the only health body to publish the expert opinion and consensus underpinning the guidelines, he said.

Revealing the underlying basis in this manner is important in a situation such as COVID-19 where there is little primary evidence available.

“There is no primary evidence, so no one really knows whether wearing a surgical mask versus an N95 masks is more effective whether its COVID-19 or even influenza. There’s very, very little primary evidence out there and the WHO as well as ANZICS have put out statements saying that primary evidence has to increase and has to improve,” said Dr Rajamani.

While the primary evidence will take a long time to compile, Dr Rajamani said there was no reason why there could not be more consistency across the different health organisations worldwide.

“We don’t know why the guidelines for the same disease need to be different between the CDC, the WHO and the ANZICS and every other organisation. Why can’t you have more harmony in the guidelines which means there will be lesser confusion? You could have one single teaching video for example for all over the world which everybody could follow. There’s no reason why that can’t happen,” he told Lab Down Under.

Image: Study infographic, part two. Used with permission.

Researchers want to help, not blame

While the study showed some countries performing better than others, Dr Subramaniam said it was not trying to place blame on anyone. Rather, he said the aim was to safeguard healthcare workers.

“We know for a fact that about 10 to 12 per cent of the healthcare workers were getting infected and that was very early in the piece. We just want to make sure that we can understand the situation to give better solutions,” he said.

Dr Rajamani told Lab Down Under that blame in an incredibly fluid situation was where the idea for the survey started.

“When you have an uncontrolled situation and you take shortages and a lack of cohesive policy, it becomes a very inflammatory situation. On social media, there was so much angst and blame. If there was a problem, it needed to be fixed because blame never sorts anything out. And that’s why we wanted to provide the data,” he said.

Survey method ‘very tight’, say researchers

The survey aimed at getting accurate data from ICUs in hospitals within the six participating countries because intensivists were more likely to be responsible for policies in each hospital, Dr Rajamani said.

With Australia, New Zealand and Singapore included from the very beginning, the researchers also decided to survey ICUs in India, the Philippines and Hong Kong. The United Kingdom and USA were also considered however they were passed over to avoid delay.

Survey results were sent out through email, social media and door knocking by on-the-ground representatives.

“We had regional leaders who were in charge of the survey in the various countries and states. Essentially they made sure that the data was collected and a reminder was sent to each of these intensivists at the end of three weeks to make sure that those who had not done the survey did it,” said Dr Ramanathan.

The response rate was 100 per cent in New Zealand and Singapore, 92 per cent in Hong Kong, 80 per cent in the Philippines, 69 per cent in Australia and 24 per cent in India.

“Despite the fact that we did it very quickly, we went through all the survey methodology tools. We initially designed the survey ourselves, we tested it on a few people in our departments, sent it out and changed the questions based on feedback. So the methodology was very tight despite the quick timeframe,” Dr Rajamani said.

Australia steps up its COVID-19 game

A follow-up survey showed that both Australia and India actually improved in the availability and use of PPE as the pandemic progressed, showing that the best way to improve a situation where there were misconceptions was through hard data, Dr Rajamani added.

“What we found is there was a remarkable improvement in Australia and in India specifically with the way they had adopted not only PPE practice and stock availability but also the education and training that goes along with it. The best improvement has been in Australia and in India by far,” added Dr Subramaniam.

While the reason behind this was because countries like Singapore, Hong Kong and New Zealand already performed well and had little room to improve in, the results were still encouraging, he added.

“What we found was overwhelmingly positive that things have changed. Have we found the right answer? We don’t know but I think we at least have some sort of satisfaction that things are improving, which means that the healthcare infection rates may come down, or at least that’s what we think.”

While this survey would not be expanded out to other countries like the UK, US or Canada, there have been studies by other research teams which looked into this. One example published in the Journal of Critical Care in October2 examined PPE safety by surveying more than 2,700 healthcare workers worldwide.

Dr Rajamani, Dr Subramaniam and Dr Ramanathan will also soon publish another paper3 looking at PPE guidelines from 40 different locations worldwide, including in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas. This research created a validation tool which can be used to assess different guidelines. The study is hoped to be published in a peer reviewed medical journal in the near future.

Researchers involved in the PPE preparedness study came from Nepean Hospital/University of Sydney, Frankston Hospital/Monash University, University of Queensland and Flinders University in Australia as well as National University in Singapore, Otago University in New Zealand, the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Aster CMI Hospital in India.

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook and LinkedIn or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Rajamani A, Subramaniam A, Shekar K, Haji J, Luo J, Bihari S, Wong WT, Gullapalli N, Renner M, Alcancia CM, Ramanathan K. Personal Protective Equipment Preparedness in Asia-Pacific Intensive Care Units during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multinational Survey. Australian Critical Care, September 2020.

2 Tabah A, Ramanan M, Laupland K, Buetti N, Cortegiani A, Mellinghoff J, Conway Morris A, Camporota L, Zappella N, Elhadi M, Povoa P, Amrein K, Vidal G, Derde L, Bassetti M, Francois G, Ssi yan kai N, de Waele J. Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID-19 era (PPE-SAFE): An international survey. Journal of Critical Care, Volume 59, October 2020, Pages 70-75.

3 Subramaniam A, Reddy M, Zubarev A, Kadam U, ZJ Lim, Anstey C, Bihari S, Haji J, Karunanithi S, Luo J, Mara N, Mitra S, Ramanathan K, Rajamani A, Rubulotta F, Svensk E, Shekar K. Development and validation of a tool to appraise guidelines on SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention strategies in healthcare workers. medRxiv, 2020.06.14, 20130682