Australian researchers have compiled the first complete historic list of avian influenza outbreaks in the country, and have warned that unless we work together and remain vigilant, a future spread of the disease could lead to massive economic damage and possible human health effects.

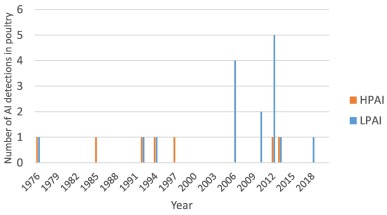

Since 1976, Australia has experienced a total of 32 avian influenza or bird flu outbreaks and detections in both commercial and backyard poultry farms. The worst of these, those with the highest pathogenic form, cost over $12.6 million in total to eradicate, and affected around 846,000 chickens, 22,000 ducks and 260 emu.

As lead author of the paper1 now published in One Health, the University of Sydney’s Angela Scott collated the data, creating Australia’s first complete list of avian influenza outbreaks, and reviewed the risks to the country’s commercial poultry industry of being hit with another virus attack in the future.

Avian influenza: A one health disease

Speaking to Lab Down Under, Scott said the motivation for creating this resource was the fact that, while each outbreak had been documented previously, information was scattered around and difficult to find.

It was essential to have a central publication such as this available for poultry veterinarians and other interested parties, she said.

“I think it’s important to note our history of avian influenza in Australia. We haven’t had an event for a number of years, so I think it’s just a timely reminder that this disease can still occur and that people need to remain vigilant for now and the future.”

One key lesson to learn from the history of avian influenza was that it was an unpredictable event, something which Scott called a “one health disease” which could spread from wildlife to domestic animals and potentially even to humans (being a virus which has what’s known as zoonotic potential).

Monitoring for bird flu is currently being conducted across Australia by specialists looking at the droppings of wild birds as well as vets examining poultry in commercial farms and backyards, Scott told Lab Down Under.

Australia’s luck and preparedness

While avian influenza has caused massive economic damage, billions of bird deaths and hundreds of human deaths worldwide, Australia has so far been fortunate by effectively eradicating all historic outbreaks.

Overseas, the virus has managed to mutate into a highly pathogenic form on numerous occasions, moving from poultry into wild birds which then spread the disease across countries and continents. This chain of events has not occurred here in Australia, Scott said.

“We’re lucky here that for most significant exotic diseases such as avian influenza, we have a plan called the Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN) which clearly documents what actions need to be done,” she told Lab Down Under.

“It’s just really handy that this plan was developed prior to disease events so it can just be picked up and ready to go. That’s really helped with the timeliness of responding to a disease event and being able to eradicate it.”

While the number of bird flu outbreak detections has increased since 2006, Scott said this was because we were testing more in Australia rather than because of any increase in the prevalence of the virus itself.

Image 1: The number of avian influenza detections in domestic poultry in Australia by pathotype (highly pathogenic avian influenza [HPAI] and low pathogenic avian influenza [LPAI]) per year. Picture by Angela Scott. Used under the Creative Commons licence.

The worst of a bad bunch

The key types of avian influenza viruses to watch for were the H5 and H7 sub-types, Scott said.

The H itself stands for hemagglutinin, a surface protein found on the influenza virus. In all, there are 18 sub-types named H1 through H18, with each affecting the characteristics of the virus itself.

Regarding avian influenza, the H5 and H7 sub-types allow the virus to replicate into a highly pathogenic strain, mutating from a virus which causes only mild symptoms into something which has a high chance of killing the bird it infects.

“So most influenza viruses circulate amongst our wildlife in a low pathogenic form, but the specific sub-types H5 and H7 can mutate to this high pathogenic form, and that’s where we see high mortality, high deaths and potential transmission to humans,” Scott said.

While the H5 and H7 sub-types were of concern for bird flu, other sub-types could result in highly pathogenic strains for influenza in other species. For instance, the H1 sub-type led to the 2009 swine flu pandemic which spread from the United States across the globe.

The problem with free-range poultry farms

With poultry farms mostly located inland, avian influenza is more likely to be transmitted to domesticated chickens and ducks from wild waterfowl rather than shorebirds.

Free-range poultry is at a higher risk of being infected by low pathogenic bird flu viruses than poultry in commercial farms which were kept indoors away from exposure to wild bird populations, the research found.

Scott said that free-range poultry production caused other issues for chickens as well, including higher mortality rates from predators, increased stress leading to illness such as parasites and bacterial diseases like spotty liver disease, and environmental degradation.

“Consumers need to understand that a century ago, we did have free range production but the chickens were moved into cages for a reason. It wasn’t to be intentionally cruel. It was to improve animal health. If you look at the literature, diseases such as spotty liver disease were noticed a century ago but then disappeared because birds were moved into cages. Now it’s reappeared.”

An increase in stress was because chickens had evolved from jungle fowl which were used to living under a canopy of trees. Without tree cover, the additional light could cause stress for free-range birds, Scott said.

Furthermore, placing a chicken into a cage with 10 or 20 other chickens allowed the birds to naturally develop a pecking order, something which was impossible to do in a free range farm where they mingled with up to 10,000 other chickens.

These cages are not the typical battery cages previously used but are what are now called ‘colony cages’ which contain around 10 to 20 birds and include features such as perches and scratching areas for the chickens, Scott said.

Preparing for future outbreaks

The paper outlined a number of key measures required to prevent future bird flu outbreaks, including continued disease surveillance, techniques to deter waterfowl from farms, agricultural planning which spread farms out, and policies to prevent the sharing of farm equipment.

Scott said it was up to government and farmers to work together to prevent these kinds of disease events in the future. One way to do this was through a government-backed liaison who could bring the various types of farmers in the poultry industry together.

“In the poultry industry, you have have egg producers, meat producers, duck farmers, chicken farmers — that sort of thing. None of them talk to each other so it’s really the government’s role to bring them all together and to educate them about biosecurity,” she said.

If all farmers understood that biosecurity was a shared responsibility, Australia would have fewer disease events in the future which would benefit the entire industry.

Further research into wild bird migration patterns was also required, as was broader avian flu surveillance across Australia, Scott said.

There was also an urgent need for more funding into what was called the ‘human-wildlife interface’, she told Lab Down Under.

“I think the one health approach has really been highlighted with COVID-19 where there needs to be more collaborative effort between human health, animal health and environmental health.

“Because avian influenza expands across all those different disciplines, it’s of real importance that there is more attention in the environmental and animal health spheres because that will have an impact on human health.”

One way of doing this would be to form a zoonotic working group that brought together experts from these three spheres from each state and territory to discuss which actions needed to be taken and where funding needed to go, Scott said.

“I think that’s the sort of thing that we need to better prepare ourselves.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook and LinkedIn or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Scott A, Hernandez-Jover M, Groves P, Toribio JA. An overview of avian influenza in the context of the Australian commercial poultry industry. One Health, Volume 10, December 2020, 100139.

Featured image: Picture by Image by Bernd Focken from Pixabay. Used under the Simplified Pixabay Licence.