Those migrating to Australia from overseas may be at lower risk of eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia than individuals born here, according to new research which suggests support for a phenomena known as the ‘healthy migrant effect’.

The research1, conducted by scientists at Western Sydney University and the University of Newcastle and published in Eating Behaviors, compiled survey data from over 6,000 individuals aged 15 years and above from 2015 and 2016.

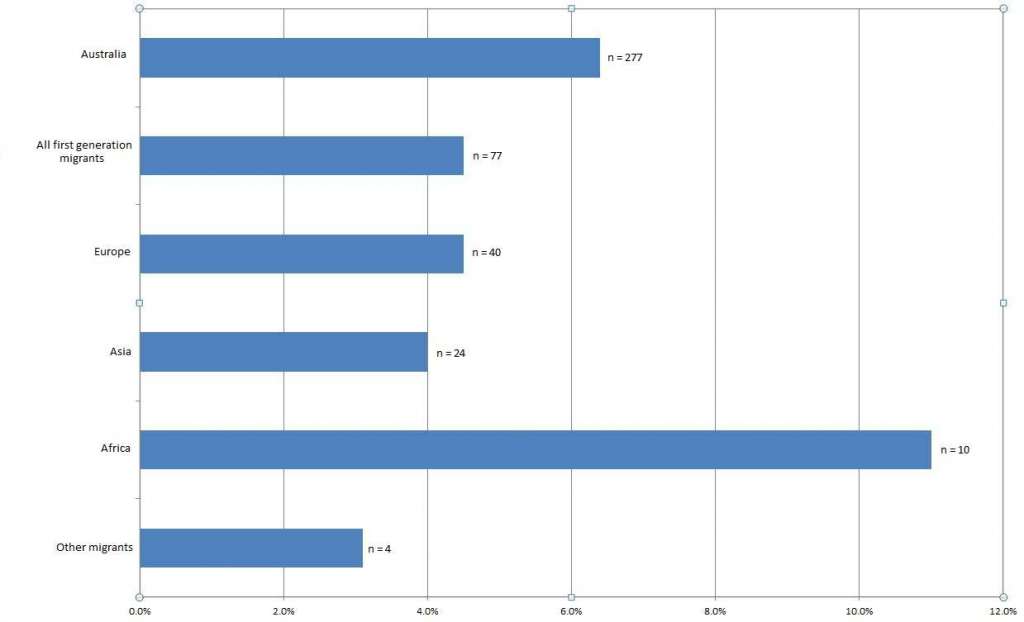

Out of the wider survey, 354 individuals reported eating disorders. 277 of these were born in Australia while 77 were migrants, with the research finding eating disorders in 4.5 per cent of first generation migrants and 6.4 per cent of those Australian-born.

Psychiatrist and first author of the paper, Dr Su Lynn Cheah, had a personal connection to the topic, being a migrant from Malaysia herself. She sat down with Lab Down Under to discuss the study and what it revealed about migrant trends for those choosing to move to Australia on a permanent basis.

Healthy vs exhausted migrants

The finding that eating disorders were less prevalent in migrant populations within Australia backed up what is known as the ‘healthy migrant effect’. In this, migrants moving to countries like Australia, Canada, the USA and the UK generally had better health outcomes than their host population, Dr Cheah said.

“The theory is that a lot of these countries accept economic or labour migrants. These are often people who are adults who have to pass some training in order to move countries and who want to migrate in the first place. They’ve got a built-in tendency to be a little bit healthier at baseline than people who choose not to migrate,” she said.

From previous studies conducted worldwide, the healthy migrant effect seems to last for one or two decades before the health of migrants can drop off and become worse than the host population. This latter trend is known as the exhausted migrant effect.

These effects related to migration as a factor on its own, Dr Cheah said, and had nothing to do with the individual ethnicity of each migrant.

Changing perceptions of eating disorders

While prior Australian research found that levels of mental disorders were lower in general in migrants than in those born in Australia2, the area of eating disorders had not been extensively studied before, Dr Cheah told Lab Down Under.

One 2002 study3 had looked solely at women, finding that migrants from European and English-speaking countries experienced the same level of disordered eating behaviours as Australian-born individuals, while those from non-English countries had lower levels.

However, Dr Cheah said that much had changed regarding culture, eating disorders and globalisation in the almost 20 years since the study was published.

“With those changes comes the revelation that eating disorders are everywhere; they’re not just in the West. And it’s not very clear whether that’s because other countries have picked up the western conceptualisation of eating disorders or whether those things were always there but just hadn’t been identified,” she said.

A predicted trend discovered

In light of this knowledge gap, Dr Cheah and her fellow researchers looked at data from 6,000 participants in the Health Omnibus Survey, a face-to-face community survey that has been conducted every year in South Australia since 1991 that is based on Australian Bureau of Statistics census data.

“After randomising a household, an individual would be identified and asked to answer the survey. That included our eating disorder question but also questions on other health data such as exercise and other things that were being tracked,” she said.

The results of this survey backed up the hypothesised view of the healthy migrant effect, that eating disorders were less prevalent in migrant populations at least as first.

“Our initial hypothesis was that levels would be lower in migrants based on the literature, but to be honest I was surprised when we actually did find that it was lower. We thought this is what we were going to find because the last study from Scandinavia — which doesn’t usually report a healthy migrant effect — also showed it was lower there. And you know, Scandinavia isn’t Australia,” Dr Cheah said.

Looking into specific groups, ages and disorders

While the survey responses showed different results for various ethnic groups — for instance, African migrants exhibiting higher rates of eating disorders than Australians and migrants from other areas — Dr Cheah was cautious with drawing conclusions from this because of the way the information was gathered in the survey.

Image 1: Three-month prevalence of any form of eating disorder in Australian-borne compared with first-generation migrants as a group and according to region of birth. Data from Cheah study1

“We were chunking a lot of different countries together into continental groupings or regions of birth in the survey. We found that there were quite high numbers among the African born group compared to the Asian born group when you compared them in the statistical testing,” she said.

“But again the numbers for those groups were quite small and we don’t know which countries in Africa they came from. That’s certainly something I’d be interested in looking at in more detail, but it’s hard to comment on that based on the study.”

Dr Cheah said she was also interested in looking at different ages of migrants from different countries and examining rates for specific eating disorders as well.

“I would really like to break that down in terms of, if migrants are less likely to get certain eating disorders, which eating disorders they are getting, when in life they might be vulnerable or resilient to these disorders, and how that might change over time.

“There’s a bit to unpack there, but I’d like to look at specific disorders – anorexia, bulimia, binge eating disorder – and see how that breaks down in migrant groups in different sets of migrants and understand where that is in young people versus older people.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Cheah SL, Jackson E, Touyz S, Hay P. Prevalence of eating disorder is lower in migrants than in the Australian-born population. Eating Behaviors, Volume 37, April 2020, 101370.

2 Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess P, Pirkis J, Saw S. The mental health of Australians 2. Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. 2009.

3 Ball K, Kenardy J. Body weight, body image, and eating behaviours: Relationships with ethnicity and acculturation in a community sample of young Australian women. Eating Behaviors, 3(3), 205-216.

Featured image: It’s all a matter of perception. Picture by Laura Lewis. Used under the Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) licence.