Researchers have found that more frequent extreme weather events caused by climate change may put dolphins at risk of death through the harmful freshwater skin disease which causes severe skin legions in these majestic sea dwelling mammals.

A study1 involving scientists from Murdoch University examined the deaths of four coastal bottlenose dolphins who succumbed to freshwater skin disease which is caused when these animals are taken out of their natural saltwater environment and suffer detrimental effects.

The research, which was also conducted with California’s Marine Mammals Centre and Victoria’s Marine Mammal Foundation, was the first time this relatively uncommon disease had been examined in Australian dolphins with scientists confidently pointing to a link between climate change and greater numbers of dolphins succumbing to this disease worldwide.

Dolphin disease caused by prolonged exposure to freshwater

Dr Nahiid Stephens is a lecturer in Veterinary Pathology at Murdoch University and co-author of the paper. She said freshwater skin disease was causing dolphins to become sick and die in greater numbers in coastal estuarine regions globally following extreme weather events.

Freshwater skin disease occurs when there is a sudden and steep drop in salinity, or salt levels, that occurs in days with these low salt conditions persisting with weeks or months afterwards, Dr Stephens said.

“The salinity reduces as a result of a sudden, significant influx of fresh water, normally following extensive rainfalls, often following a period of relative drought.”

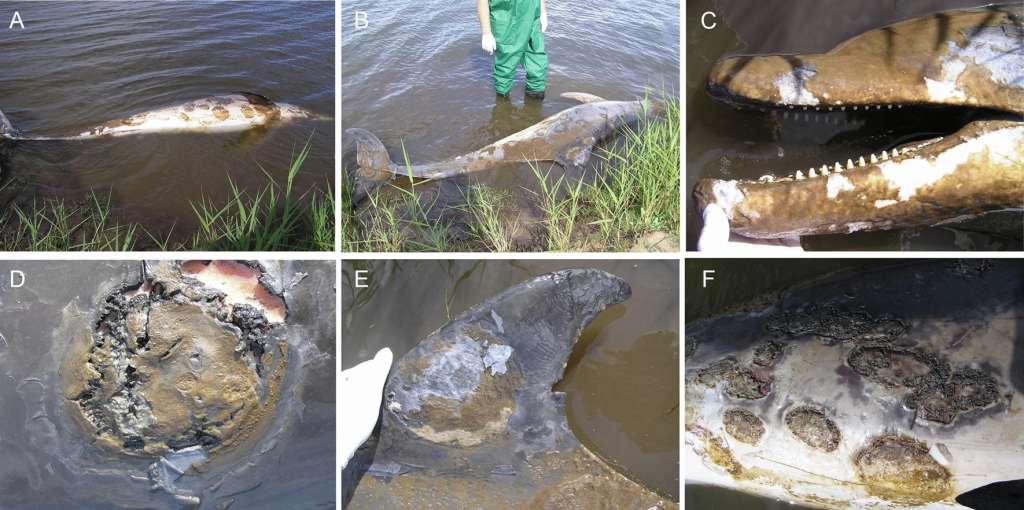

Dolphins affected with freshwater skin disease typically experience skin lesions that can form ulcers and become colonised by algae, diatoms, fungi and bacteria.

“From this, death may ensue from fluid loss and electrolyte imbalance — because the ulcerative skin lesions are akin to severe third degree burns and often affect a large percentage of the body surface. Secondary infections also play a role,” Dr Stephens said.

Image: Adult female T. australis (case 1) found dead with severe ulcerative dermatitis at Jones Bay, Lake King North, near the mouth of the Mitchell River, 29th October, 2007. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Symptoms result because dolphins living in these environments have evolved to live in marine settings and are unable to adapt to sudden changes to salt levels in the water.

“Because of the rapidity of the change and because the dolphins are exposed to freshwater for a prolonged period … the freshwater causes skin damage, an influx of water into the skin causing swelling, which then progresses to inflammation and ulceration. The badly damaged skin then gives secondary opportunistic infectious organisms such as fungi, bacteria, and algae a chance to take root,” Dr Stephens told Lab Down Under.

The disease itself is “relatively uncommon” in dolphins and had never been documented before in Australia prior to these case studies, she said, adding that it had now been seen in multiple locations worldwide and was occurring more frequently.

Freshwater skin disease outbreaks occurring worldwide

Four dolphins fatalities were examined in the study, two that occurred in Victoria’s Gippsland Lakes region in 2007 and two in Western Australia’s Swan-Canning Riverpark in 2009.

“While these events are historical, they enabled us to conduct post mortems on the dolphin carcases to identify the cause of their death, characterise the severe skin lesions typical of the disease, and to see if there is a correlation between these events and others around the world,” Dr Stephens said.

A similar outbreak of freshwater skin disease was reported for the first time in the US in dolphins living in Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

In Gippsland, the outbreaks of freshwater skin disease followed the resumption of seasonal rainfall following a prolonged drought. This influx of rain flooded the marine water with freshwater.

Similar scenarios occurred in WA where unusually high winter-spring rainfall turned brackish/marine water into freshwater and also in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and Texas in the US following the aftermaths of Hurricane Katrina and Harvey.

“What they’re reporting overseas is identical to our Australian study — common to all outbreaks in all locations is a preceding extreme weather event with extensive rainfall which causes a sudden, significant influx of fresh water into an enclosed to semi-enclosed body of water, which is normally brackish to marine in nature, causing a sudden, dramatic, and persistent drop in salinity to become freshwater,” Dr Stephens said.

The scientists are confident in linking the disease to extreme weather events because changes seen in the dolphins at Gippsland and WA were identical and the proceeding environmental triggers very similar.

“Based on these findings, we are concerned freshwater skin disease is an emerging disease of [whales, dolphins, and porpoises] which we are likely to see increasing in frequency in vulnerable estuarine and coastal habitats globally that continue to be affected by worsening climate change,” Dr Stephen said.

Dolphin populations at risk in Australia included three colonies in south-west Western Australia at Perth, Mandurah and Bunbury. There is also a current ongoing outbreak affecting the endangered Burrunan dolphins off the coast of Victoria, Dr Stephens said.

“Globally, it will be (indeed, has been) a big problem in the Gulf of Mexico (USA) in particular but could affect dolphins all along the east coast of the USA. It’s less of an issue in the west USA due to the different geography. It may also arise in future in many parts of Asia. With a record hurricane season in the Gulf of Mexico (USA) this year and more intense storm systems globally due to climate change, we predict more of these devastating outbreaks.”

Eyes on the water enable world first study

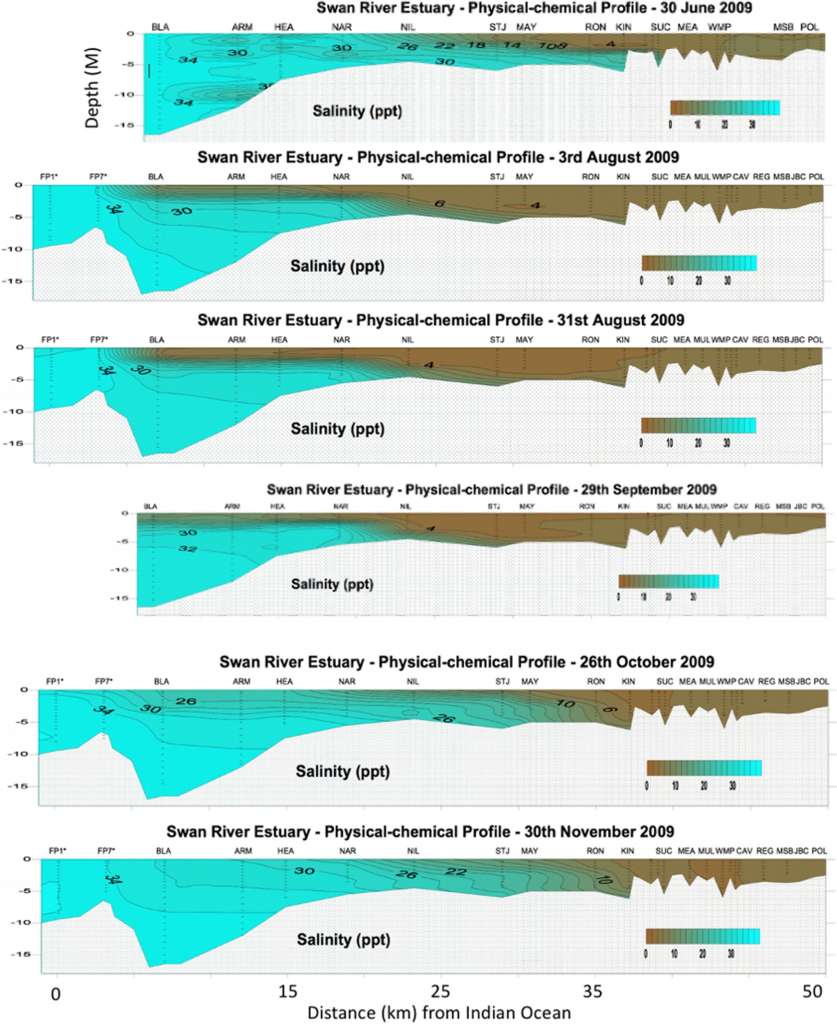

For the two Australian events, researchers were able to access data compiled by ongoing monitoring from long-term and ongoing field ecology, population, and behaviour studies to track the environment that the dolphins lived in.

“The waters inhabited by the dolphins were intensively monitored for physical and chemical parameters before, during and after the events; and when mortalities occurred, thorough and systematic post-mortem examinations were carried out, including investigation and characterisation of the skin lesions with histopathology, electron microscopy, and molecular techniques to rule out infectious causes,” Dr Stephens said.

This research was critical in understanding the nature and composition of dolphin populations in both Victoria and WA as well as the physical and chemical nature of the marine environments they were living in, she told Lab Down Under.

Image: Temporal series of water salinity plots for up to 20 sampling stations at increasing distance from the Indian Ocean (0 on lower X axis) to 50 km upstream (right of figure). Fresh water (< 5 ppt) is represented as brown colors while marine water (> 25 ppt) is blue or green. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Data from citizen science projects included WA’s River Guardians and Dolphin Watch programs was also used.

“They are educational outreach programs however there are also additional components depending on how involved people wish to become, e.g. they can take part in clean-up days, they can undertake free training to become equipped to report sightings, behaviour etc that go into a database where researchers can build up a better understanding of how different animals use different areas within the riverpark, and for what purposes,” Dr Stephens said.

“The more people who have eyes on the water and can spot report-worthy information (e.g. a new calf and who it is born to, a sick or distressed or entangled individual), the better — because no-one can be out there all the time.”

Dr Stephens told Lab Down Under she would continue to investigate strandings, deaths and disease outbreaks among Australian dolphin populations.

However, she pointed out that dolphins which lived in vulnerable coastal and estuarine regions faced multiple threats in addition to climate change including habitat loss and degradation, vessel strikes, fishing line entanglement and chemical contamination.

“My research focus is on studying these threats and the contributory role they play in cetacean disease/death, in the hope that my findings allow better mitigation of the environmental factors that we may be able to influence positive control over in order to protect and conserve these animals — and therefore, their environment — which is also ours.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook and LinkedIn or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my blogs in your inbox.

1 Duignan P, Stephens N, Robb K. Fresh water skin disease in dolphins: a case definition based on pathology and environmental factors in Australia. Scientific Reports, volume 10, Article number: 21979 (2020).

Featured image: Dolphins in the ocean. Used under the under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.