While Melbourne’s seaside suburbs today attract up-market homeowners and holidaymakers, millions of years ago they were home to a very different type of inhabitant but one no less loveable: pods of seals which are thought to have been much smaller than their modern-day relatives.

Researchers from Monash University and Museums Victoria have done a deep dive on seal fossils sourced from paleontological sites in the Melbourne suburb of Beaumaris, uncovering more about these lesser known creatures in a world where headline animals such as dinosaurs and ancient marsupials often take the limelight.

The new paper, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society1, was headed by lead author and PhD candidate James Rule from the Adams Integrated Morphology and Palaeontology Laboratory at Monash.

Rule was able to examine nine individual fossils, uncovering the characteristics of these animals for the very first time. What he discovered was that the seals of five to six million years ago living in the Beaumaris area were around half the size of seals that are found around the world today. This dramatic size difference is thought to be a product of a warmer climate millions of years ago and the food available for these ancient seals to eat.

A growth spurt over the ages

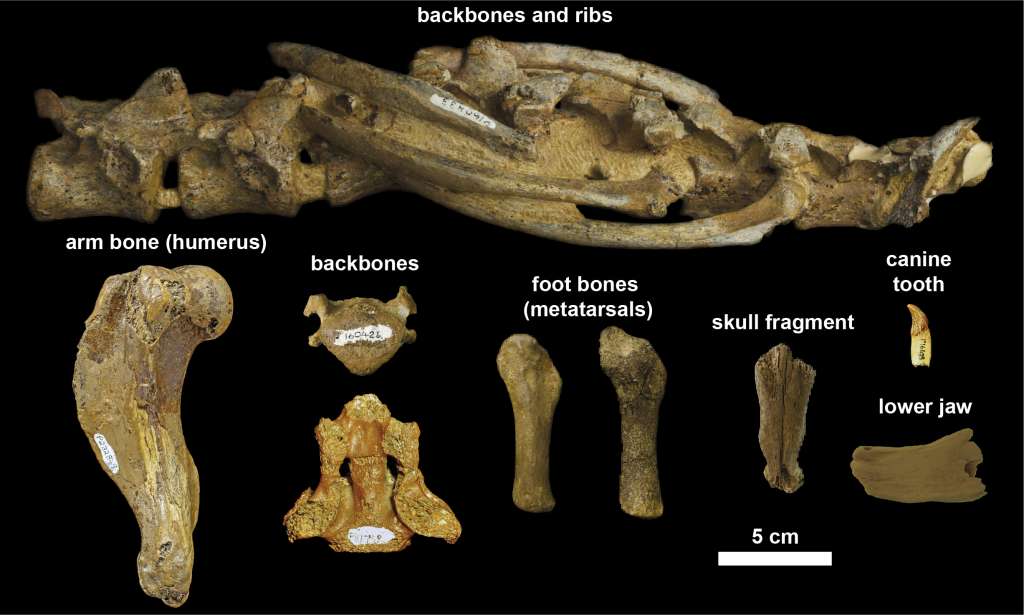

The fossil specimens, which included skull fragments, vertebrae, teeth and metatarsals (which are found in the flippers and are similar to toe bones in humans) came from the Late Miocene to the Early Pliocene Epochs (around five to six million years ago) when the Earth was much warmer and sea levels were higher.

Rule was able to pin down the classification of the individuals seals to varying degrees, some more precise than others. Two specimens did not offer much information other than being from the Pinnipedia group which contains all seals. Five (possibly six) fossils were from true seals (the Phocidae family), while one was linked to a sub-family called Monachinae, the southern group of true seals.

True seals are often also called earless seals because they do not have external ears. They are distinct from other types of seal including the walrus, sea lion and fur seal, which come from other families within the Pinnipedia group.

The seals that lived at Beaumaris were around 1.5 metres in length with characteristics very much like today’s true seals. This made them around half the size of their modern-day relatives which averaged around the three metre mark as adults, Rule told Lab Down Under.

“So what that essentially means is, for an animal such as a seal, that’s a substantial increase in body length and body size. If you get a seal that’s even a metre longer, that seal would have more blubber or more fat,” he said.

While the site at Beaumaris was only a little bit further south five million years ago due to continental drift, it would have been deeper underwater due to the warmer climate at the time.

“A warmer world essentially means you have less water trapped in ice at the polar ice caps and that leads to a higher sea level. So the higher coastlines of these areas would have been remarkably different to what they are today,” Rule said.

Image 1: Fossil site at Beaumaris. Picture by Erich Fitzgerald. Used with permission.

Weight loss tips for seals

Rule postulated that there were two reasons why seals in the past were smaller than they are today, although he admitted this was speculation and that further research was required.

Because the climate was much warmer when these seals lived five million years ago, they did not have to have as much blubber as the seals today, he said.

“If you’re an animal with a larger body size and you have a lot of blubber, you tend to conserve heat a lot more. If you live in a warmer ocean, that essentially means you’re going to overheat. So being large is a very beneficial adaptation in the Southern Ocean around the Antarctic but it’s not so good in warm areas near the tropics.”

Secondly, the size of predators like seals depends on primary producers such as plankton and plants which lie at the bottom of the food chain. In colder environments, these primary producers tend to be a lot larger than their counterparts in warmer regions, Rule said.

“If you live in a colder environment, there are going to be more energy efficient food chains where there are larger animals to eat and therefore you can reach a larger body size easier,” he told Lab Down Under.

“In a warmer environment, these primary producers tend to be a lot smaller. That means predators need to eat more of them in order to maintain the energy needs of their body size, which usually ends up meaning that animals tend to be a lot smaller.”

Image 3: James Rule with articulated fossil seal backbone. Picture by Yestin Griffiths. Used with permission.

‘Seal fossils are actually extremely rare’

Rule’s research fills a very large gap in what scientists understand about seal fossils found around the Southern Ocean. While there have been fossil seals found in South America, South Africa and Australia, very little was known about the animals themselves because of a bias paleontologists had in this field towards the Northern Hemisphere.

One reason behind this is that seal fossils generally are quite rare, Rule said.

“Seal fossils are actually extremely rare. They’re not just rare in Australia and New Zealand, they’re rare around the entire world. So at sites where you should find seals, you usually only find a lot of shark fossils and whale fossils. No one really has a clear idea of why this might be,” he told Lab Down Under.

“Seal fossils just aren’t very common. Because there aren’t as many fossils that means there aren’t as many experts, and so most of the research on prehistoric seals has occurred in the Northern Hemisphere.”

In fact, there has only been one prior paper2 on a seal fossil from Beaumaris, and that was published in the 1983 by Professor Tim Flannery in his time before he became an environmentalist. Flannery discovered a fossilised seal ear bone while diving at Beaumaris.

As well as the Beaumaris site, fossil seals had only been found at two other sites in Australia, both of them located in Victoria, near the towns of Portland and Hamilton.

While there were other potential sites in Australia were seal fossils may be found, no one had made this discovery yet, Rule said.

Fragments of a family tree

In order to pin down exactly what families and groups these ancient seals came from using only their fossils, Rule had to become familiar with the entire skeleton of different types of modern seal and then compare the features of the fossils with actual bones from these present-day relatives.

“I did that by spending a lot of time in museum collections, not just in Victoria, but also at other institutions like the Smithsonian and the London Natural History Museum. I sat in those collections and collected data on what characteristics of their bones could be used to identify them as a particular type of seal.”

Image 3: Fossil seal specimens. Picture by James Rule. Used with permission.

Fossil specimens with particular defining characteristics could help pin down which family or sub-family that specific seal belonged to when alive. Those without any unique qualities did not permit Rule to classify them in any more specific group than just Pinnipedia, or seals generally, however.

With the specimens available, Rule was unable to classify any fossil seals according to their species or genera.

“We can lock them into these more broader groups but usually they have to be very complete in order to identify them to a genera or species,” he said.

Specimens such as backbones can’t help pin down the type of seal specifically because they don’t help observers understand much about the animal itself and how it lived. What is required are “information heavy” bones such as skulls or more complete skeletons, which come with a great many defining characteristics.

Dreaming of seal skulls

Rule is now continuing his seal research, examining Beaumaris and other fossil sites around Australia, and hopes to visit Beaumaris when the COVID-19 lockdown measures permit.

“One of the dreams I have at the moment is hoping to find the skull of a seal at Beaumaris. We do have fragments of skulls that have been found there, but unfortunately they’re not complete enough. I hold onto hope that we’ll one day find a skull at the site,” he said.

“There’s also another site nearby in Melbourne’s Bayside called Site B which we’ve recently discovered within the last few years, and so we’re also going to be looking for seals from there as well. We hold onto hope that this new site will produce more seal fossils.”

Rule is also examining prior fossil specimens found at Beaumaris in the 1980s to make sure that they have been correctly classified in line with today’s updated scientific knowledge.

“Now that the taxonomy of seals, the way that we identify seals, has progressed a little bit more, I’m going to go back to these specimens and figure out if there is a way that we can get a more specific diagnosis with the knowledge that we have now of seal anatomy.”

Fossil digs at Beaumaris are funded by donations from the Lost World of Bayside, an initiative run by Museums Victoria which helps uncover fossils of seals, whales, sharks and other marine creatures from ages past. Rule himself was funded by Australian Government RTP Stipend scholarship and a Monash University–Museums Victoria Robert Blackwood Partnership PhD scholarship.

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook and LinkedIn or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Rule J, Adams J, Fitzgerald E. Colonization of the ancient southern oceans by small-sized Phocidae: new evidence from Australia. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa075, 17 August 2020.

2 Fordyce RE, Flannery T. 1983. Fossil phocid seals from the late Tertiary of Victoria. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 95: 99–100.

Featured image: Seals at Melbourne’s Bayside Five Million years Ago. Picture by Peter Trusler. Used with permission.