A group of hydrogeologists has launched a volley against what they call the sidelining of science by Adani Mining and the Federal and Queensland Governments in the approval of the highly controversial Carmichael coal mine.

In a new paper published in Nature Sustainability1, scientists from RMIT, Flinders University and the University of Queensland write that Adani was not required to conduct the proper investigations of the mine and assess its risks to the 150 wetlands in the Doongmabulla Spring complex, located eight kilometres away.

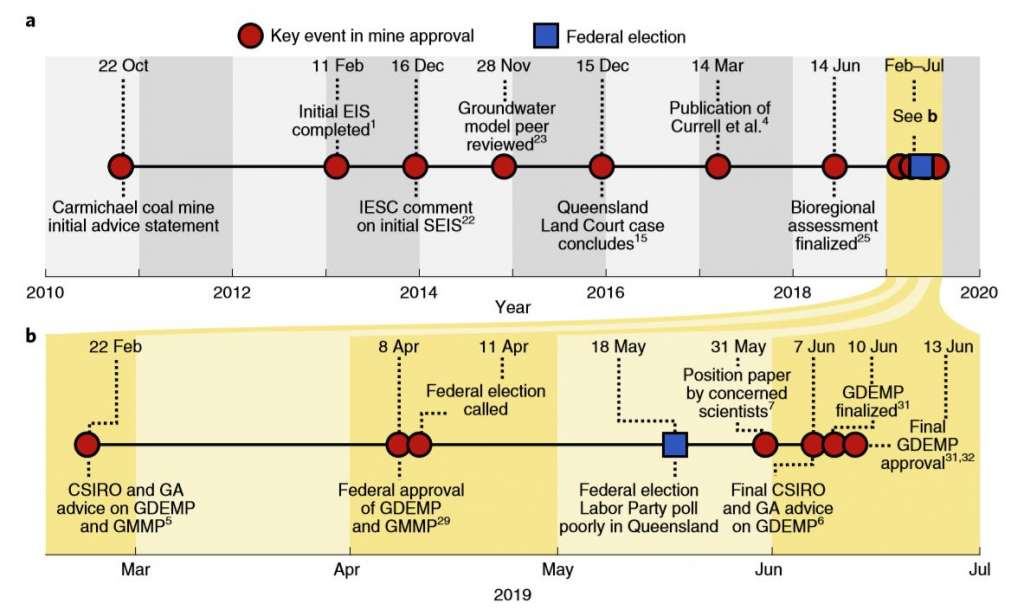

The paper reviewed the timeline in the lead-up to the mine’s approval in mid-2019 after nearly a decade of environmental assessments and legal challenges, including a swathe of scientific reports which were examined by the state and federal governments as well as the Land Court.

Dr Dylan Irvine of the College of Science and Engineering and National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training at Flinders University was an author on the paper. He sat down with Lab Down Under to discuss how the scientific evidence was pushed aside in the approval process and what this may mean for the groundwater systems of the Doongmabulla Springs.

The best science, used but ignored

The piece in Nature Sustainability examined the various reviews submitted ahead of the mine approval, highlighting the major issues raised within and the poor way in which those issues were dealt with.

“In a nutshell, at several times during this process, key issues had been identified and as far as we were concerned they had never been addressed yet the approval process seemed to be progressing,” Dr Irvine said.

One review of the mine was conducted in 2013 by the Independent Expert Scientific Committee on Coal Seam Gas and Large Coal Mining Development (IESC). This was followed by two reports by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and Geoscience Australia.

“The IESC review was fairly scathing. We feel that a lot of issues that were pointed out back in 2013 remain today, yet the mine is approved. Then there were the two reviews by CSIRO and Geoscience Australia which also highlighted several deficiencies.”

The government’s overall messaging around the Carmichael mine approval process also was not entirely accurate, Dr Irvine said.

“At several times throughout this process, we would hear in the media that the best science is being used in the decision-making process. From what I saw, maybe the best science was being used but then it was also being totally ignored.”

A tale of two aquifers

The specific deficiencies in Adani’s groundwater analysis came from the way in which the firm interpreted where the water in the Doongmabulla Springs came from and the effect that its mining operations would have on that water source, Dr Irvine said.

“At this stage, we don’t know categorically where the water from the Doongmabulla Spring complex comes from. So we don’t know, Adani doesn’t know, CSIRO don’t know — we don’t know categorically where that water comes from,” he told Lab Down Under.

Image one: Joshua Spring in the Doongmabulla Springs. Picture by Dr Dylan Irvine. Used with permission.

What is known is that there are two main groups of aquifers which lie under the ground that are separated by a layer of thick claystone material. The deeper aquifer units contain the coal seam, which Adani will access by drilling down and pumping out the water beforehand.

In Adani’s version of how the springs work, the water is sourced entirely from the upper aquifers. This means that the coal in the deeper aquifers should be able to be mined relatively safely without disrupting the outflow to the springs.

However, it is possible that the deeper aquifers are the source of the springs as large faults or cracks in the claystone layer have been recorded and could act as a pathway from the water located deep under the ground up to the surface, Dr Irvine said.

‘There’s a high chance that those springs will dry up’

Adani had done its best to ignore the scenario where the spring water was sourced from the deeper aquifers, Dr Irvine told Lab Down Under.

“All of their work has been based on the fact that all the water of the springs comes from these shallow units. So the issue here is that if those springs do source some of their water from the deeper units when the mine goes ahead, there’s a high chance that those springs will dry up.”

The problem was further compounded because Adani did not have an adaptive management strategy for what to do if the water levels dropped, instead saying in 2015 during a Land Court case2 that it would merely formulate a plan if this situation occurred, Dr Irvine said.

“That’s not adaptive management. In adaptive management, you have to consider all the possibilities and you have to have a plan in place for what you’ll do.”

Adani’s groundwater modelling was also tweaked to back up the company’s assumption that the shallow unit was the source of the water and that the mining operations would not influence the springs, Dr Irvine added.

Reports from the CSIRO and IESC showed that this modelling was not supported by the data, he said.

“What Adani should have been doing is collecting more data to back up their position. But they were reluctant to do that.”

If the springs do dry up, this will affect the plants and animals that are dependent on that groundwater source and will also affect the local indigenous people who view the springs as a spiritual location.

Political pressure for approval

Despite these discrepancies between Adani’s modelling and reports from the CSIRO and IESC, the mine was approved in mid-2019 with assistance from both the Federal and Queensland State Governments.

“This is a rare case where the Federal Coalition and the state Labor government were on the same page. It was very obvious that both governments wanted the mine to go ahead. You can understand that they wanted the jobs that go along with the mine. So it seems to be that a lot of the political process was engineered to make that result possible,” Dr Irvine said.

The 2019 Federal Election itself was a “strong motivating factor” for the mine’s approval, he added.

“There was a flurry of activity immediately before the election. So there were certain approvals that the Federal Government wanted to get through before they called the election, because obviously there were things that they couldn’t do in caretaker mode.”

Just after Labor lost to the Coalition, the Queensland State Government tasked the CSIRO and Geoscience Australia with creating a second review for the mine, in what the paper describes as “political interference”. However, the two agencies were only given a short timeframe of three weeks to complete the review and were told only to answer a very limited set of questions.

“They didn’t have the ability to raise any additional concerns at that point. Our take on that is that it doesn’t seem genuine to go and seek a review but to really restrict what the scientists can do in that review process,” Dr Irvine said.

Image 2: Timeline of the Adani mine approval process including steps in the Groundwater Dependent Ecosystem Management Plan (GDEMP) and the Groundwater Monitoring and Management Plan (GMMP). Picture from Science sidelined in approval of Australia’s largest coal mine. Nature Sustainability, May 2020.

A scientific body with teeth

To prevent science like this from being ignored in the future, Dr Irvine suggested that an organisation like the IESC be created which had actual power to request work be done.

“As far back as 2013, the IESC made some pretty scathing observations of the work that Adani had put together but there was no onus on the company to address any of the concerns that the IESC had put together.”

All three agencies — the IESC, CSIRO and Geoscience Australia — had highlighted some “pretty severe shortcomings” in the approval process for the Carmichael mine, but these were swept aside, Dr Irvine said.

The proposed body would avoid this type of scenario, being able to review these types of cases and require that any suggestions or issues raised actually be addressed, he added.

Concerned scientists without a political bent

The piece in Nature Sustainability was a follow-on from a 2017 position paper3 written by Professor Adrian Werner, Associate Professor Andy Love, Dr Dylan Irvine and Eddie Banks (Flinders University), Professor Ian Cartwright (Monash University), Professor John Webb (La Trobe University), and Associate Professor Matthew Currell (RMIT University).

This previous position paper criticised the way that the President of the Land Court Carmel MacDonald had handled the scientific evidence in her judgment2 rejecting a legal challenge to three mining leases granted to Adani over the Carmichael mine.

Professor Werner was an expert witness in the Land Court case while Dr Chris McGrath of University of Queensland was a lawyer acting for Land Services of Coast and Country Inc, a former charity organisation which opposed the grant of the leases in court.

Both Professor Werner and Dr McGrath were authors on the newer Nature Sustainability piece.

Dr Irvine noted that despite the political nature of the paper, he was not affiliated with groups such as Stop Adani or the Greens.

“I’ve seen people labelling us as anti-coal or anti-coal propagandarists or whatever the phrase is. The key thing for me is that’s not our position at all. In this case, we’re not talking about climate change and we’re not talking about jobs. We’re talking about the hydrological science and we think that best practice hasn’t been followed,” he told Lab Down Under.

“I just want to make it clear that we want the best science to be used in decision-making processes. Now governments can ignore scientific advice. That’s something that they can do. But we would like them to be open about that process — so not to claim that the best science is being used when they are doing their best to keep some of the science out of the story.”

Author’s note: If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Lab Down Under on Facebook or support me on Patreon. I also have my own personal Twitter account where I’ll be sharing my latest stories and any other items of interest. Finally, you can subscribe here to get my weekly blogs in your inbox.

1 Currell M, Irvine D, Werner A, McGrath C. Science sidelined in approval of Australia’s largest coal mine. Nature Sustainability, May 2020.

2 Adani Mining Pty Ltd v Land Services of Coast and Country Inc & Ors [2015] QLC 48

3 Werner A, Love AJ, Irvine D, Banks EW, Cartwright I, Webb J, Currell M. Position Paper by Concerned Scientists: Deficiencies in the scientific assessment of the Carmichael Mine impacts to the Doongmabulla Springs. June 2019.

Featured image: Key documents in the Carmichael mine approval process. Picture by Dr Dylan Irvine. Used with permission.